| Zooming into the Past |

|

THE CHARCOAL TRADE AND ENVIRONMENTALISTS

Workers turning trees into charcoal by burying woods into the pit and setting ablaze.

Indian vessel MV Safina Al Basirat, charcoal carrier, docked at the Old Port of the Kenyan coastal city of Mombasa

Environmentalist Fatima Jibril,

Environmentalist Who Returned From USA to Salvage Forests

Dorothy Otieno June 26, 2002

Fatima Jama Jibril first left her country Somalia when she was 16. She accompanied her mother to join her father in America, where she pursued her high school education and joined business school.

After completing her studies she returned to Somalia in 1969 and briefly worked at the Treasury. But on getting married to Ali Abdulrahman, she returned to the US, where she bore and raised her five daughters.

She settled peacefully in America until the events following the 1991 ouster of President Siad Barre jolted her into action.

At the height of the civil war in Somalia, Jibril and her family watched on American television the horror and suffering of their people back home.

DETERMINED: Jibril hopes to put a stop to the environmental degradation taking place in her country.

"As I watched the unfolding chaos, I prayed that somebody would liberate Somalia," she says.

America led an international peace keeping force into the country but the mission failed. Jibril realised that if things were to change, Somalis had to influence the change themselves.

She and other like minded Somalis in America formed Horn Relief to positively contribute to change in their motherland.

In 1993, Jibril and her husband volunteered to return to Somalia.

"While people were fleeing into exile, we were headed in the opposite direction," she says.

Recently, when she was visiting Sanaag, a remote village in Somalia, she heard on radio that she had won this year's Goldman Award, the highest grassroots environmental prize. The prize was awarded on April 2, in San Francisco, USA. At first she thought it was a hoax.

"I thought it was one of the many fraud plots in America," she confesses.

She did not know anybody was paying attention to her environmental campaign in Somalia.

The annual Goldman Award, which includes a cash prize of US$125,000, is given to six people, one per continent.

The candidates are people who work within communities to protect the environment through seeking solutions to environmental problems and lobbying for positive environmental policies.

Among the past recipients of the award is Green Belt movement co-ordinator, Prof. Wangari Maathai.

Jibril received the award in recognition of her work with Horn Relief, which she founded to rehabilitate forests and marine resources in Somalia.

On returning to her homeland, Jibril was shocked at the level of environmental degradation. Growing up in a pastoral community, she spent her childhood roaming the countryside grasslands. She found a desert where the grasslands had existed.

She discovered that forests had been destroyed for charcoal that was sold in the Gulf.

"With no central government to administer national resources, people are cutting down every tree in sight," she says.

"Some of the trees felled are 50 to 100 years old. Despite protests by environmentalists, Gulf nations continue to participate in the plunder of the country's natural resources," adds Jibril.

"If this trend continues, there will soon be no pasture for the Somali nomads," she warns.

She says that fishing companies from the European Union are taking advantage of the situation to fish along the Somali coastline, destroying the coral reefs in the process.

To effect positive environmental change in Somalia, Horn Relief trains the community in the management of natural resources.

They are trained in rainfall management techniques, to utilise the draining into the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea.

"Youths are trained to build rock dams using pebbles, around the country."

Horn Relief focuses on the youth whom they hope to engage in beneficial activities other than being fighters for the warlords.

"The environment is not just about trees and soil, it is holistic. This is why we are helping pastoral youths to organise themselves and work together," she says.

"Somalia is basically a desert and inhabitants must learn to share water and other resources, otherwise our country will never know peace," she adds.

Jibril hopes that by participating in the activities, the youth will learn to govern themselves in a respectful manner and the approach is bearing fruit.

In the village of Badan, two sub-clans are working together to build and rehabilitate village roads. Horn Relief also lobbies different organisation to support environmental development matters.

A year ago, the organisation convinced administrators in Puntland, one of the regional administrative areas in Somalia, to pass laws banning charcoal exports.

Jibril hopes to work with other regional administrators in the country to achieve the same.

Although the international community has not responded to the issues by Horn Relief, Jibril hopes their voice will be heard one day.

"There is no room for despair as life is about hope and if we lose it, we all die," she says.

She is encouraged to continue her crusade.

Her determination was instilled in her by her mother who worked for 17 hours a day as a small scale trader while her husband was in England.

"My mother had little education but believed life was about making choices," says Jibril. One of these choices was to send her to school in a community where education for girls was discouraged.

Jibril is also the co-ordinator of Resource Management Somali Network, an organisation that brings together Somali environmentalists.

© The East African Standard. Distributed via COMTEX News.

To Fuel the Mideast's Grills, Somalia Smolders

By MARC LACEY 25 July 2002 Page 4, Column 3

MOGADISHU, Somalia -- Before it ends up in a grill somewhere in the Middle East, searing lamb or beef, Somalia's ''black gold'' travels a perilous road from acacia forests in rural areas to one of the country's busy ports.

Charcoal is perhaps the biggest export of this rugged country, so collapsed that statistics are among the many things hard to come by. Once, acacias covered vast swaths of Somalia's south and central regions; today, the forests are devastated. Despite an official ban on the export of charcoal, truckloads of it clog the dangerous roads to port bound for Saudi Arabia, Yemen and the United Arab Emirates.

''Because of the lack of a central authority, illegal deforestation has become big business,'' said Abdulkadir Yahya Ali, director of operations at the Center for Research and Dialogue in Mogadishu. ''It's a lucrative way for gangs to make money. They are making money from the collapse of a state.''

Abukar Abdi Osman, the environmental minister for the makeshift government in Mogadishu, declared an end to charcoal exports when he took office this year. His predecessor had done the same thing last year, to little avail.

''It's not good for the country,'' Mr. Osman declared. ''We now have sand covering areas where there used to be forests, and there is less ground for livestock to graze.''

The minister, member of a government whose control does not even extend throughout the capital, has resorted to taxing charcoal shipments, a step that he says will eventually allow him to seize the trucks and ships that carry charcoal and arrest the dealers getting rich from it.

As it is now, Mogadishu's main charcoal market operates less than a mile from the hotel that Mr. Osman uses as his offices. The market is a grimy place, where Somalis born with dark brown skin turn completely black during the workday from the dusk of the coal.

The workers separate large shards, which will bring top dollar, from the tiny pieces. And they load truck after truck, often piling the charcoal so high that the bumpy roads inevitably cause bits of black gold to fall to the road.

To turn trees into charcoal, workers dig a huge pit, bury the wood and set it ablaze, but only limited oxygen is allowed into the fire. What results are shards of charcoal.

The charcoal trade is one of many assaults on Somalia's environment. Toxic wastes were dumped into many rivers years ago by foreign companies unafraid of government regulators. Wildlife, once plentiful in Somalia, has been killed with such abandon that there is believed to be relatively little left. But Mr. Osman's crew of six, charged with monitoring a country about the size of Texas, is barely able to identify the extent of the environmental devastation, never mind do anything about it.

The former government of Said Barre, which fell in a coup in 1991, had banned the export of charcoal, and imposed stiff enough penalties on violators that few made a living off the trade.

Even in the early days of Somalia's descent into chaos, when Gen. Muhammad Farah Aideed controlled parts of the south of the country in the early 1990's, he continued to ban logging.

But after he died in 1996 and his son, Hussein Muhammad Aideed, replaced him, charcoal exports soared, driven by the simple logic of economics: a bag of charcoal that sells in markets here for $4 fetches $10 or more in Arab countries that have banned their own production of charcoal for environmental reasons.

A decade ago, the United Nations estimated that 14 percent of Somalia was covered with woodland. Some experts say that figure may now be as low as 4 percent. As for charcoal production, the United Nations estimates that 112,000 metric tons were produced in 2000, of which 80 percent went abroad. Exports of charcoal may have overtaken those of bananas, once a major source of foreign currency for Somalia.

Livestock exports have long been hindered by a ban imposed by various Arab countries on camels, sheep, goats and cattle, ostensibly because of concerns over animal health. So, instead, Somalia sells the charcoal with which Arabs grill their meat.

Somalia is rugged, with little arable land. It is believed to be rich in iron ore, tin, bauxite and uranium, perhaps even in petroleum and natural gas reserves.

For now, though, charcoal is Somalia's only precious material, and it allows thousands of low-paid laborers to make a living.

''It's very dangerous, but it's how I survive,'' said Hassan Ali Farah, showing a stump where his left thumb used to be, chopped off in an ax accident, and a nasty burn on his chest, the result of a charcoal fire that went awry.

Another danger that workers like Mr. Farah face are the land mines scattered through the Somali countryside in years of war.

Most of the charcoal profits go to the traders and the faction leaders who control access to the forests. To these men, environmental damage is of secondary concern.

''It's one of the main businesses in the country,'' said Ali Gulied Mahed, 58, a middleman who was standing beside several dozen fully loaded trucks at Mogadishu's main charcoal market.

To men like him, the economics are simple: the trees are free and the labor is cheap. A ship laden with 100,000 sacks of ''black gold'' has $1 million in cargo, a haul that is typically traded for the many goods that Somalia lacks.

Although most of Somalia's charcoal is sent overseas, it remains the main cooking fuel for Somalis. Throughout the country's previous export bans, local use has always been permitted.

But in the past, axes were used to fell the trees. Now that charcoal has become a big business, forests buzz with the sound of chain saws.

''The charcoal problem is really a symptom of the far greater problems we're facing,'' said Mr. Ali of the Somali research institute. ''These are armed, irresponsible guys who are ruining the land because they want to eat.''

© 2002 New York Times Company

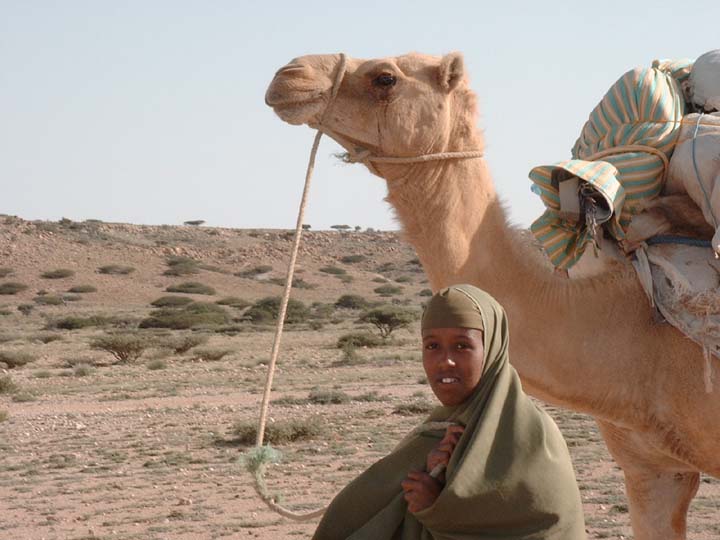

Khadro, a Horn Relief staff person, leads a camel through a typical Sanaag pastoral backdrop.

environmental degradation

|