Suicide of a Nation

Somalia descends

into inferno of

chaos

By

Paul Watson

February 16, 1992

The Toronto Star

MOGADISHU

-- Something has

snapped in Somalia.

After three months

of civil war that

has killed and

wounded at least

30,000 people, the

country's soul is

dying. People here

are so used to

staring into war's

hideous face that

too many have lost

the horror. The

brutal fighting is

now their chief

entertainment.

Some 400,000

terrified Somalis

have fled for their

lives.

Many live in the

desert in tiny

beehive huts made of

scrap metal and

cardboard bound

together with rope

and rubber straps.

Thousands more

civilians have

stayed in Mogadishu,

braving machinegun

fire and artillery

barrages that batter

the city each day.

In a residential

district controlled

by the guerrilla

leader trying to

oust Somalia's

interim president,

hundreds of people

turn out to see the

street battles close

up. Even kids ignore

the sharp crack of

assault rifles,

crowding sidewalks

near the frontline

to watch tanks blast

the next

neighborhood. As the

country commits

suicide, spectators

cheer each explosion

while families of

the dead and wounded

weep.

It is the Hobbesian

vision come true, a

society collapsed

into anarchy, a

savage, pitiless

world where life has

become nasty,

brutish and short.

People who once

loved and laughed

and hoped like all

of us now think only

of staying alive one

more day, of saving

enough strength to

survive another.

It's a miracle that

so many still can.

The barbarity is

beyond exaggeration.

Somalia hasn't had a

government or police

for more than a

year. Most people

haven't had a job or

a regular paycheque

for even longer.

Thousands of

convicts who escaped

from jail amid the

chaos run amok with

assault rifles and

machineguns,

shooting anyone who

gets in their way.

The few drivers

still on the road

have to fill the

back seat, and often

the open trunk, with

armed guards for

protection.

At night, the city

is pitch black

except for the

intermittent flash

of artillery. There

hasn't been any

electricity for

months, nor is there

any running water in

most of the city.

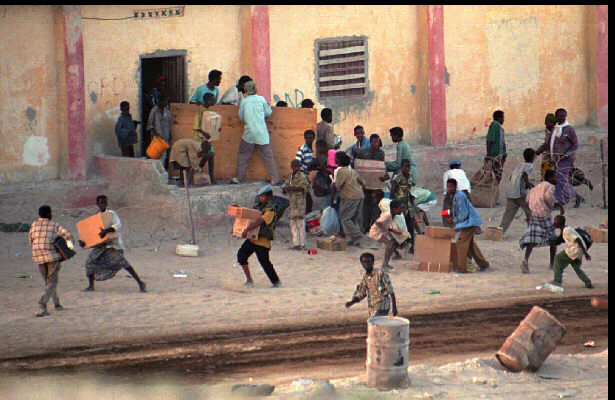

Looters hacked down

all the hydro wires,

dug up the water

mains and sold them

in neighboring

countries along with

the cars, computers,

phones, light

fixtures and

truckloads of other

booty they stole at

gunpoint.

Thousands of

refugees living in

the desert around

Mogadishu can draw

water from wells but

they have no food

and can't afford to

buy any. Most are

trying to survive on

tea and scraps of

bread.

In the small section

of Mogadishu still

controlled by the

country's nominal

president, Somali

surgeons operate on

war casualties in

abandoned houses. In

one living-room

operating theatre, a

woman was lying

unconscious on a

wooden table while a

surgeon rooted

around in a gaping

wound in her abdomen

picking out bits of

shrapnel.

A wide-eyed little

boy was wandering

around the operating

room, stretching up

on the tips of his

bare toes to see the

man with half his

cheek blown off. The

windows beside the

operating table were

wide open so glass

wouldn't fly across

the room if an

artillery shell

exploded nearby.

No one on the

surgical team wore a

mask. There's no

point worrying about

germs in a room

about as sanitary as

a garage. A rattling

old fan whirled next

to the operating

table, bothering a

swarm of flies just

enough to keep them

out of the open

wound. While a

volunteer nurse

mopped up pools of

coagulating blood,

more victims lay

moaning and bleeding

on the floor.

The skilled Somali

surgeons do their

best, Western relief

workers say. But

they have no

training in war

surgery and often

make terrible

mistakes, such as

sewing up wounds

that should be left

open to drain.

Gangrene often sets

in and victims end

up losing limbs, or

dying when they

could easily have

been saved.

The international

Red Cross, the only

relief agency that

crossed the

frontline to put

physicians into

northern Mogadishu,

was converting an

empty prison into a

well-equipped field

hospital.

But the Red Cross

workers had to flee

the area Thursday

after guerrillas

bombarded the only

airstrip. Dozens of

people were killed

or wounded as the

mortars rained down

in the stepped up

assault. Some of the

bombs hit the very

houses where

surgeons were trying

to keep the wounded

alive.

Fierce fighting

resumed in Mogadishu

yesterday morning,

just hours after

representatives of

the two main warring

factions signed

separate commitments

to stop fighting

after talks at the

United Nations.

On a continent

synonymous with

civil war and

starvation, Somalia

was supposed to be

different. It's an

African oddity, a

country where

everyone belongs to

the same ethnic

group, speaks the

same language and

adheres to the same

religion: Islam.

Yet that common

cultural thread

wasn't enough to

prevent the country

from unravelling

into a tangled mess

of rival sub-clans

ruled by petty

warlords.

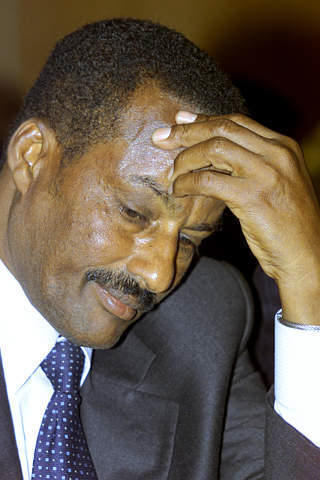

Ali Mahdi Mohamed, a

hotel owner named

interim president of

Somalia at a meeting

of guerrilla groups

last July, says he's

defending his

government against a

coup.

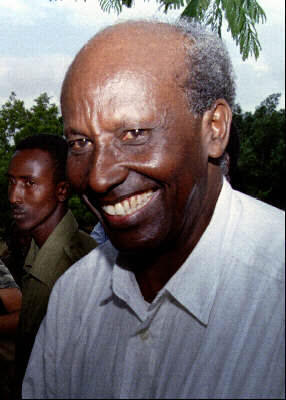

Gen. Mohamed Farah

Aideed, the

guerrilla leader who

helped oust former

dictator Mohamed

Siad Barre a year

ago, insists Ali

Mahdi is a crook who

must be arrested and

put on trial.

Ali Mahdi says he

would gladly meet

Aideed in court and

vows to fight to the

end keep the general

from seizing power.

"We lost thousands

and thousands of

people for

democracy,"

Ali Mahdi said

during a recent

interview in his

northern enclave.

"We will not accept

again a military

dictatorship

The combined

destruction of the

battle to remove

Barre and the past

three months of

urban warfare has

left about 80 per

cent of Somalia in

ruins, according to

Ali Mahdi.

Even if he and

Aideed ever agree on

a formal ceasefire,

it's hard to imagine

their followers

simply falling into

line and laying down

their arms. Most of

them aren't

disciplined troops

dressed in uniforms.

They're wild

warriors who fight

for pillage,

pleasure and some

perverted sense of

honor.

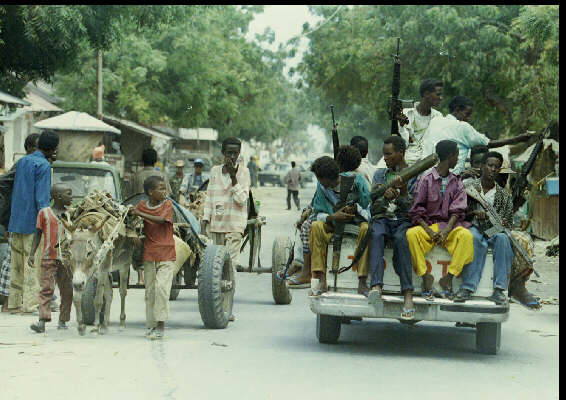

Thousands of gunmen

cruise the city day

and night like

barracudas on a

hunt. Most have a

crazed glint in

their eyes from

chewing bundles of

ghat, a bitter plant

that delivers a

sharp amphetamine

kick. Even little

boys no older than

10 carry loaded

rifles and give

orders at

checkpoints in this

bizarre war zone.

Only foreign troops

could restore order

and disarm Somalis,

maybe by buying

their weapons with

food, Ali Mahdi

argues.

But Aideed refuses

to accept outside

intervention,

probably because he

holds the upper hand

in the battle for

control of

Mogadishu.

Besides, the general

says with a wry

smile, Somalis are

very attached to

their guns.

"Traditionally,

Somalis love very

much weapons, horses

and camels. Most of

our people are

nomads, over 70 per

cent in rural areas,

and the weapons can

be used for self-defence.

Many times people

also give rifles as

a gift or dowry to a

family when they are

asking to marry."

For centuries,

Somalia was a

desolate land of

nomads with little

to offer the world

except camels and

frankincense, one of

the Magis' gifts to

the newborn Christ.

But during the Cold

War, Somalia had

something new for

sale: naval bases

for superpowers

competing to control

access to the Red

Sea's oil shipping

lanes.

As the Soviets and

Americans bid for

Barre's favor, one

of the poorest

countries on Earth

built up a massive

army and air force

equipped with some

of the best killing

machines on the

market. Now the

fighters and bombers

are wrecked and

rusting on the

tarmac, so the

guerrillas found a

new use for four-barrelled

anti-aircraft guns

that can pump out

about 600 rounds a

minute. They shoot

them at people.

Somalia's acting

U.N. ambassador,

Fatun Mohamed

Hassan, begged the

United Nations

Security Council

last week to hurry

up and do something,

anything, to end the

madness.

"Let me assure the

council that any

measures - even if

coercive - to

resolve the current

crisis in Somalia

cannot and will not

be interpreted as

interference in our

internal affairs,"

he said. "The Somali

people (are)

pleading with you to

stop the bleeding of

their country."

� Copyright 1992 The

Toronto Star

U.N. warrior has

nightmares about

Somalia

By

Peter Smerdon

February 16, 1994

MOGADISHU,

Feb 16 (Reuter) - He

landed a gung-ho

warrior to save

Somalia from

warlords looting

food aid. He leaves

a year later for

home next month,

bitter and troubled

by what he saw.

The United Nations

Operation in Somalia

(UNOSOM) set

conditions for a

journalist to

interview its

peacemaker. He could

speak candidly but

had to be identified

only as a U.N.

military official.

His country, rank

and job were not

allowed to be given.

Looking back

uncomfortably on his

year in a land he

hardly knew before

arriving, he says he

has

nightmares about the

Somalia experience.

The Security Council

has finally scaled

back its grandiose

drive for aggressive

peacekeeping. UNOSOM

will limp on for a

year after the

United States and

other mainly Western

forces pull out by

the end of March.

But the alarm bells

for renewed civil

war are already

ringing.

The original aim of

UNOSOM to push

reconciliation and

reconstruction was,

the official says,

the logical next

step for this

war-shattered Horn

of Africa country

after the end of the

famine, which

prompted U.S.

intervention.

But then came

problems. Warlord

Mohamed Farah Aideed

and his Somali

National Alliance (SNA)

opposed U.N.

intervention.

"There was a (U.N.

and U.S.) lack of

recognition of what

problems there were.

Has it been a total

failure?...To the

SNA people, UNOSOM

would have failed

whatever happened,"

he says.

"In that regard

conflict was

inevitable. It

started as a

political and

propaganda conflict

and then became a

military one, which

was inevitable

because the SNA

wanted it that way."

"We began taking

casualties on June 5

(last year) and took

them at the rate of

one per day," he

says. "The SNA of

course took vast

numbers of

casualties and the

militias were

strained to breaking

point.

"But they had the

advantage of time.

They could protract

the conflict...They

knew the coalition

members couldn't

afford politically

to take casualties

in Somalia. The

populations at home

weren't prepared to

accept casualties

for this mission."

He says U.S. forces

again miscalculated

by thinking they

could easily

overcome Aideed's

200 rag-tag

militiamen. And as

the U.N. body count

kept rising, its

will to fight waned.

"We could have

captured Aideed. A

military solution

has a cost and when

the conflict began

it wasn't clear what

the cost was," he

says and pauses. "It

became very clear on

October 3."

"We learned the

cruelties of war.

Compared with the

Gulf War this was a

real war. It was up

front and personal,

right in front of

your eyes," says the

official, who

accompanied units in

combat.

"In the Gulf War it

was watching a TV

screen and the bombs

going in. You didn't

have to think what

happened to the

people in the

building when it was

hit.

"But here, you saw

the faces close up

of the people in the

building. You saw

the women and

children killed,

and the women and

children used as

human shields.

You saw them

dragging American

bodies through the

streets. There was

nothing hidden.

"All the ugliness of

war was right there

slap in your face.

And there is a

certain ugliness to

war...It was much

more distasteful in

Somalia than any

other U.N. action up

to now.

"And the SNA knew

that. The SNA knew

that just to keep

killing would unify

the world (to pull

its U.N. forces

out)."

He has special

hatred for Aideed,

who for four months

evaded a U.N.

manhunt featuring

Wild West-style

$25,000 reward

posters for his

capture. After 18

U.S. servicemen were

killed in a battle

on October 3 the

United Nations

abandoned the

search.

"Was the decision to

capture Aideed

flawed? When it was

made a full

understanding of the

consequences was not

realised... They

certainly had the

capability to take

casualties among

U.S. forces.

"We couldn't

overcome them with

just firepower," he

says.

The U.N. retreated

from its ambitious

role-model for

peacekeeping

operations in world

troublespots after

President Bill

Clinton ordered a

total U.S.

withdrawal by March

31 and tried to

court Aideed to talk

peace.

The official says:

"All the propaganda

in the world will

never erase the fact

that Aideed is a

criminal, a murderer

and a warlord.

He killed thousands

of his own people

even before the U.N.

arrived here.

"If

you ask a Somali

about Aideed he

doesn't say he has

built hospitals. He

hasn't done a single

thing for the

people. They know he

is a murderer. He

got off lightly. And

in the end it never

mattered that he got

away with murder

here."

Asked whether he

believed the Somalia

mission could never

have succeeded, he

says everything

depended on the U.N.

will.

"There will always

be the potential for

battles as long as

there are Somali

terrorists who still

don't want UNOSOM in

Somalia,"

he says. He accuses

the U.N. of awarding

building contracts

to a SNA-controlled

corporation to

appease Aideed.

Asked if withdrawing

U.S. forces would

hit back against a

large attack, he

says he thinks they

would only leave

faster.

"The response to a

massive attack would

only be political. I

don't think that we

are going to destroy

anymore. We're on

our way out. We

aren't going to kill

anyone, anymore."

©

1994 Reuters Limited