| Zooming into the Past |

|

M O G A D I S H U C I V I L W A R S

Introduction

Zooming into the 1990s interviews and statements, given by the spokespersons and leaders of Somali factions, enables us to prove that clan-animosity account of the Somali civil war has not been given the scholarly attention that its magnitude warrants, even after sixteen years of clan-warfare. This clan-animosity feeling can in fact be derived from faction joint communiqué and statements; and therefore, posting selections of these public relation statements should be a matter of concern to all Somalis – particularly, to those who are in the field of Somali Studies.

After all, clan factionalism disguised in English acronyms (formed from three or four initial letters which include the sacrosanct letter “S”) are now facts of life for Somalis. The words and deeds of the turbulent faction followers have ordained to presuppose that faction spokespersons assumed a monumental role in fuelling clan-hatred. As a result of that, the Forum rushes in to investigate and share with you excerpts of faction communiqués, hoping to find solutions to the current tragic political situation in Somalia. From our perspective, these selections are indeed those that Western scholars/(Somalists) most neglected, or could offer hints to the causes of the civil war.

J A N U A R Y 1 9 9 2

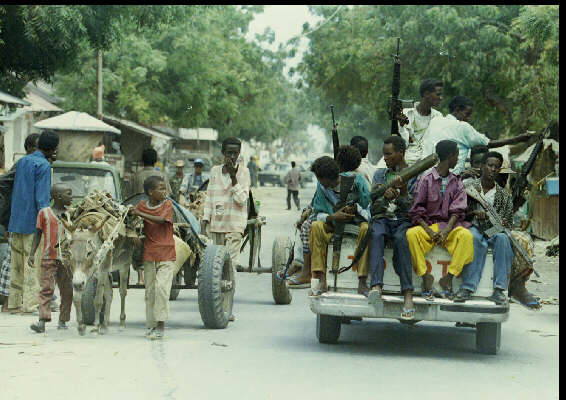

Somali gunmen drive through the streets of Mogadishu

OLD MAN BEGS FOR HELP FROM SOMALI GUNMAN IN CITY OF BAIDOA, SOMALIA

A young Somali smokes and holds a weapon as he and his friends sit on a car

Children pulling a donkey cart watch a carload full of armed militiamen pass through the streets of Mogadishu

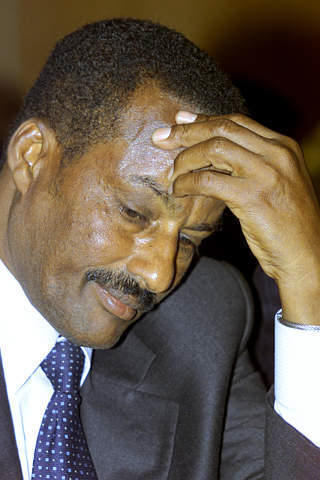

General Aidid Interviewed on Mogadishu Plight

London BBC World Service in English 1705 GMT, January 07, 1992 [From the "Focus on Africa" program]

[Begin recording] [Aidid] I think a peaceful solution is near. Already, a plan of meeting has been fixed in the next edition.

[Biles] But the reality on the ground seems somewhat different because the fighting is going on, there is shelling and gunfire in the background even as we speak. You refused to have anything to do with your opponent, Mr. Ali Mahdi. Why do you rule out the idea of outside intervention, perhaps, the UN peacekeeping force coming in?

[Aidid] We do not see any solution to bring in these forces or foreign intervention forces in Somalia, in USC areas because we believe we are able to settle our problem by our own. We are working hard, and the results will be seen by everybody.

[Biles] How much longer do you think it is going to go on then?

[Aidid] Inside USC problems, I think it would be a few weeks.

[Biles] Have you been into any of the hospitals yourself? Have you seen the result of this conflict, this carnage?

[Aidid] Yes, I have seen and I hope these killings will be stopped by those who are committing this crime.

[Biles] If you do not accept the presence of the UN peacekeeping force, would you accept some kind of outside intervention to allow humanitarian aid to be distributed?

[Aidid] We are asking the humanitarian aid to be distributed to the needy people. We have made a lot of appeals and we hope the international community will answer.

[Biles] Mogadishu is short of food, it is short of medical supplies, it is short of fuel, almost everything is in short supply. But one thing, Somalia is never seen to run out of is ammunition.

[Aidid] We are not receiving any ammunition or any arms from outside. We are using only the ammunition and the armament we have taken previously from Siad Barre regime. [end recording]

A dirty little war 5,000 DIE IN CIVIL WAR

By Richard Dowden January 05, 1992 Independent On Sunday

You don't have to be a soldier to get yourself killed in Mogadishu. Many of the 5,000 men, women and children slaughtered in the seven-week-old Somali civil war have been caught in the random fire of rival armed bands divided by neither race nor politics. This is another dirty little African war, fought with guns supplied by superpowers whose interest ceased when they could no longer see a strategic profit.

"Of course no one cares," the UN diplomat fumed. "It's Africa - it's not strategically important, it's not Yugoslavia, it's not Russia. It doesn't mean anything."

For the last seven weeks, Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, has been a city of slaughter - the scene of relentless, unimaginable destruction equalling, if not exceeding, the wreck of Vukovar or Beirut in the scale of its mayhem and murder. "At Benadir hospital... who counts the numbers coming in?" asks David Shearer, the field director of the Save the Children Fund in Mogadishu. "They keep arriving, bits blown off - arms, legs, guts, brains. Sometimes the doctors are paddling in blood. It's a complete shambles."

He will not put a figure on the numbers who have died. He reckons there were between 120 and 130 a day immediately after the fighting erupted on 17 November; now there are about 75 a day. Other aid workers estimate that 4,000 to 5,000 people have died in the past seven weeks - putting the death rate at 100 a day.

In fighting of this sort, the casualty rate is usually about three times the death rate. Just before his retirement from the secretary-generalship of the United Nations last week, Javier Perez de Cuellar put the figure at 20,000.

At one level, the reason for the conflict is that the United Somali Congress, the movement which overthrew President Siad Barre in January, has split and the two wings are fighting each other for control of Mogadishu.

Half a million people used to live in the city. Some have fled - maybe 100,000. The rest huddle in their barred and bolted homes, venturing out only to find essential food and water. Most of those who have died are civilians, women and children, torn by shrapnel or hit by bullets fired a mile or two away in street battles.

It is not a question of getting caught in crossfire: 105mm shells and tank rounds are fired into the city indiscriminately - sometimes as many as 300 or 400 a day - and heavy machine gun bullets can still smash through the flimsy walls of homes two or three miles from where they are fired.

The victims are brought into the city's four hospitals in donkey carts or even wheelbarrows. The Somali doctors, unpaid for months, operate in shifts, exhausted and short of medical supplies. Conditions are described as disgusting. In the north of the city, which has taken the heaviest shelling, there are no facilities at all and the Red Cross is trying to turn a disused prison into a hospital.

Fighting is now concentrated around the radio station - to announce on the radio that you are in power is almost to be in power. The station stands next to the heaps of rubble of what used to be the presidential palace. That, along with most of the city centre, was destroyed in January.

Mogadishu itself used to be a pleasant Indian Ocean port built around a maze of narrow streets of low whitewashed houses encompassing an ancient Arab souk. Later, during fascist Italian occupation, preposterously grandiose Roman facades were added, but now it is - or was - mostly a mixture of solid, unimaginative blocks for the bureaucracy and acres of flimsy dwellings for the poor.

The two men whose soldiers are fighting each other for control of the city are General Mohamed Farah Aideed, the chairman of the USC, and Ali Mahdi Mohamed, the interim president. General Aideed's heavily armed troops have invaded the city from the south, but they have been unable to defeat or drive out the supporters of President Ali Mahdi, who controls the north of the city.

There is no government. Most of the President's government, including the prime minister, are on a long mission out of the country. They live in the Sheraton Hotel in Djibouti, the neighbouring country.

During the day, General Aideed's troops pour shells into areas inhabited by Mr Ali Mahdi's supporters and attack their positions. By night, the President's fighters creep back and ambush General Aideed's men. Observers say there seems little sense or strategy on either side.

For anyone visiting the city there is a bewildering profusion of weapons carried by very young men whose allegiances are not immediately obvious. When the army barracks were looted, nearly everyone obtained a gun - the presence of equal numbers of AK-47s and M-16s symbolising the country's fluctuating relationships during Siad Barre's 20-year rule.

The young fighters' favoured vehicle is the pick-up truck with a 50mm machine gun mounted on the back. Many of them move in gangs, seemingly loyal to no one but themselves, preying on the weak, looting at will and killing at random. Their cheeks bulge with wodges of khat, a mild narcotic leaf. When they smile that distant smile or speak in a slow, deliberate way, they expose teeth stained green. Without a daily chew, addicts become paranoid and aggressive. They will kill for a bunch of khat leaves - or less. There are some extremely dangerous people on the streets of Mogadishu.

But it is also dangerous to leave. Abandoned houses are immediately looted, and beyond the city boundaries there are bandits: no one really knows what is happening elsewhere in southern Somalia, but without a central power it is likely that much of it has degenerated into banditry and the settling of old scores. Refugees from the town are easy prey.

There is no electricity in Mogadishu, and in the northern districts of the city there is no water either. Water is pumped into the southern half from a station controlled by an independent group whose power resides in their ability to destroy the remaining fuel for the station's generator. They have threatened to blow it up if they are attacked. Food, of course, is scarce, and commands three or four times normal prices. The currency is the old 1,000 Somali shilling note - worth #20 five years ago, now worth about 7p. There are no telephones, and the only communication with the outside world for about 30 aid workers who have stayed on is the satellite phone or radio link.

General Aideed's forces will not allow shipments of food aid to land at the docks, and last month they forced a Red Cross ship to return to the Kenyan port of Mombasa. Recently a Belgian Red Cross worker, Wim Van Boxelaere, was deliberately and casually killed while trying to negotiate food distribution. The Somali who threw himself across Van Boxelaere to protect him also died.

Only the occasional Belgian air force Hercules manages to land medical and other essential supplies for the Red Cross and the other three aid agencies - Medecins sans Frontieres, the Save the Children Fund and SOS Children's Villages - remaining in the capital. But the agencies have given up trying to negotiate food distribution beyond the hospitals. All diplomats and most other westerners have fled.

Who are these people? Why do they do this? These are not questions to which the rest of the world has hurried to find answers. Unreported because of events in Russia and Yugoslavia, Somalia has been watched with indifference or incomprehension. And for outsiders it may be incomprehensible.

There is something uniquely Somali at the heart of the conflict. It is the only country in Africa with only one ethnic group, one culture, one language and one religion, yet it is torn by deeper hatreds than other African countries riven by ethnic and language differences.

Somalia's civil war is rooted in the ancient rivalries between the vast and complex clan system which makes up the Somali nation, persisting through the period of colonial rule - by the British in the north and the Italians in the south - which lasted from the 1890s until joint independence in 1960.

Most Somalis come from a nomadic tradition. The land is harsh, arid, unforgiving, and it made the Somalis. In the past, camels were the currency of existence, and stealing camels - and, sometimes, women - from neighbouring clans was the national sport.

Complex rules and intricate procedures governed whose camels could graze where and when, and allowed for the intervention the elders, who would step in and negotiate when the young warriors' games got out of hand. In the open land the nomads could steal, fight and run. Conflicts could remain unresolved. The great tradition of Somali oral poetry is full of lays of battle, death and revenge, a culture of war passed on by relentless repetition by the camp fires under the stars.

When the British explorer John Hanning Speke, one of the first foreigners to set foot in Somalia and live, arrived there in 1855, he remarked: "There is scarcely a man of them who does not show some scars of wounds... some apparently so deep that it is marvellous how they ever recovered from them." And you can see that tradition in their eyes today as the young Somali warriors thrust out their guns and pump off a few rounds into the air to impress the visitor.

For Somalis, Somalia is the centre of the universe and their clan politics are the sole, absolute and eternal meaning of a life in which ideology or democracy have no place. In 1975, President Barre was forced to switch his allegiance away from Moscow (which had been strategically interested in the Somali port of Berbera, but moved on to the more valuable target of Ethiopia), under whose aegis he had imposed a destructive and brutal socialism. Now he courted Washington, sharing out his country's wealth among his friends and suppressing any opposition as ruthlessly as he had in his socialist days.

His rule was never about ideology but about control, and he ruled Somalia through a skilful manipulation of the clan system. Eventually he ran out of allies. In the north the Somali National Movement, formed mainly by the Issaq clan, struggled against him for 10 years. When he was overthrown, the SNM restored a measure of peace and order and last May declared independence from the south. Somalia is now divided along the old colonial boundary.

In the south, opposition movements came and went until the USC began to draw the Hawiye clan into rebellion. Led by General Aideed, the USC drove steadily towards the capital, and on 27 January last year Siad Barre fled.

It was not General Aideed's forces, though, but an uprising in Mogadishu which finally caused Siad Barre to flee, and before the USC leader could take the capital another administration had been installed. The capital fell into the hands of the Manifesto Group, consisting largely of businessmen who had tried unsuccessfully to persuade Siad Barre to resign. They elected President Ali Mahdi, a local hotel-owner who had served as a member of the post-independence Somali parliament in the 1960s, as interim president. General Aideed felt betrayed.

President Ali Mahdi is from the Abgal sub-clan, who live as cultivators and traders in the well-watered areas around Mogadishu. They are the main group in the capital and many of them benefited from Siad Barre's rule. They had a lot to lose.

Even by lofty Somali standards, the Habar Gadir have a superiority complex. They look down on the Abgal as weak and soft, seeing themselves as the natural leaders of Somalia, a warrior caste whose time has come - a self-image reinforcing General Aideed's belief that he was the victor in the war against Siad Barre and is therefore his rightful successor. The Abgal, however, see the Habar Gadir as invaders, trying to take over their city, which has been in the hands of alien clans since independence. They are fighting for their homes, their city and their lives.

"Now, after the total 'clan-isation' of the society, the Abgal see themselves as the owners of Mogadishu and the surrounding area," Professor Samatar reflects. "They're more numerous than the Habar Gadir, though less well armed, but they've sworn to control Mogadishu. They're not a warlike people, but they feel they've had to put up with nonsense from everybody, and now it's time to claim their birthright."

Behind them, meanwhile, the traditional Habar Gadir territory has been taken over by two other clans, the Omar Mohamud and the Leelkase - so the Habar Gadir have nowhere to go back to. For them, defeat simply is not an option.

How will it end? Judging by the way they spray bullets with abandon, both sides appear to have plenty of ammunition. The looted barracks were once bulging with Russian and US weaponry left over from the Ogaden war of 1977-78; they have since been restocked by Washington and, most recently, Colonel Gaddafi.

Then, last May, more guns and bullets came in from Ethiopia, after the overthrow of President Mengistu, brought across the border in truckloads by ethnic Somalis from the Ethiopian army and by Ethiopians who were unwilling to surrender to the new government. There seems, though, to be no external arms supplier at present.

Somalia is the second country where hope born at the overthrow of a dictator was dashed as the victors fell out among themselves. In Liberia, after President Samuel Doe had been overthrown in September 1990, the capital city, Monrovia, was destroyed in a demonic orgy of killing and destruction.

That has now ended, partly because there is nothing left to destroy, partly because of a tentative political agreement, and partly through the presence of the West African peace-keeping force. The split in Liberia is political, regional and tribal, not nearly as intractable as Somalia's clan conflict.

In the past, such a dispute would have been arbitrated by elders from other clans. During his long rule, Siad Barre destroyed the power base of the clan elders as well as that of the poets and mullahs, either by buying them off or imprisoning them.

None of these traditionally respected groups can now take on the task of negotiation and reconciliation. Two small political groups, each one sympathetic to different sides, have recently combined forces to try to negotiate a ceasefire, but last Monday's broke down straight away.

In one of his final acts as Secretary-General, Javier Perez de Cuellar announced la st week the imminent departure of a special UN emissary, James Jones, to mediate between the clan warlords in an effort to end the conflict and begin relief operations. But it seems unthinkable that outsiders could negotiate between the two sides in a country where outsiders are regarded with suspicion and none is seen as impartial. So there is little chance that ceasefires will lead to a successful peace. Mogadishu's bloodshed will continue.

© 1992 Independent Newspapers (UK) Limited. All rights reserved.

SOMALI GUNMEN DRIVE THROUGH THE STREETS OF THE CAPITAL MOGADISHU

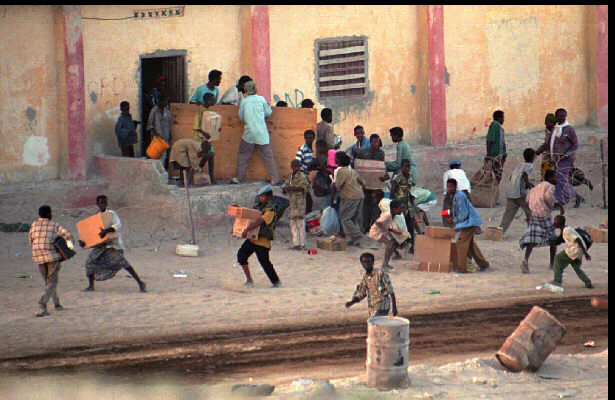

Somalis loot U.N. barracks near the Mogadishu port

|

[Text]

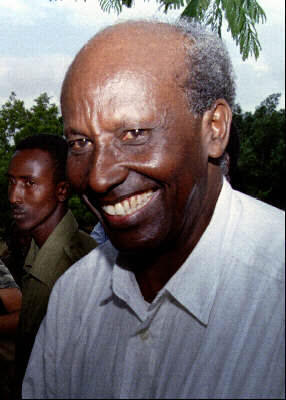

This weekend, James Jonah, the UN special envoy, ventured into the

war-torn Somali capital, Mogadishu in attempt

[Text]

This weekend, James Jonah, the UN special envoy, ventured into the

war-torn Somali capital, Mogadishu in attempt  The

quarrel between the two men is reinforced by an intra-clan war

within the Hawiye.

The

quarrel between the two men is reinforced by an intra-clan war

within the Hawiye.