| Zooming into the Past |

|

M O G A D I S H U C I V I L W A R S

Introduction

Zooming into the 1990s interviews and statements, given by the spokespersons and leaders of Somali factions, enables us to prove that clan-animosity account of the Somali civil war has not been given the scholarly attention that its magnitude warrants, even after sixteen years of clan-warfare. This clan-animosity feeling can in fact be derived from faction joint communiqué and statements; and therefore, posting selections of these public relation statements should be a matter of concern to all Somalis – particularly, to those who are in the field of Somali Studies.

After all, clan factionalism disguised in English acronyms (formed from three or four initial letters which include the sacrosanct letter “S”) are now facts of life for Somalis. The words and deeds of the turbulent faction followers have ordained to presuppose that faction spokespersons assumed a monumental role in fuelling clan-hatred. As a result of that, the Forum rushes in to investigate and share with you excerpts of faction communiqués, hoping to find solutions to the current tragic political situation in Somalia. From our perspective, these selections are indeed those that Western scholars/(Somalists) most neglected, or could offer hints to the causes of the civil war.

J A N U A R Y 1 9 9 2

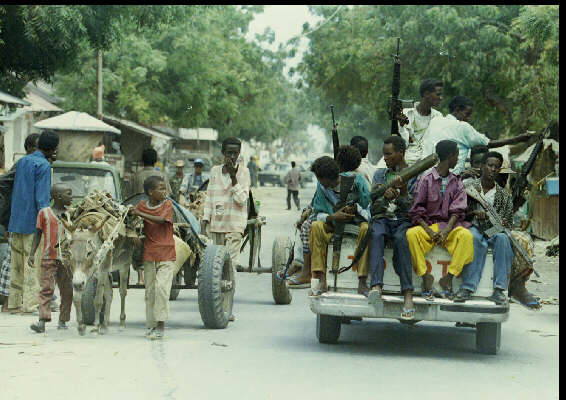

Somali gunmen drive through the streets of Mogadishu

OLD MAN BEGS FOR HELP FROM SOMALI GUNMAN IN CITY OF BAIDOA, SOMALIA

A young Somali smokes and holds a weapon as he and his friends sit on a car

Children pulling a donkey cart watch a carload full of armed militiamen pass through the streets of Mogadishu

CIVILIANS LOSE HOPE AS SOMALIA'S BLOOD FEUD RAGES

By Aidan Hartley 807 words January 15, 1992

MOGADISHU, Jan 15, Reuter - It's as if babies were scared even to be born in Somalia.

Doctors in Mogadishu, the Somali capital, say eight weeks of bloody ethnic feuding have caused a shocking rise in Caesarian births and obstructed pregnancies.

Roman Catholic Sister Maria Antonia at the SOS Kindergarten International hospital, the only maternity clinic still operating in the devastated city, has a more pragmatic explanation. "Mothers have lost hope," she says.

"Nearly every delivery has complications because they are so tense."

Most of the estimated 20,000 people killed and wounded since a power struggle erupted between rival warlords Mohamed Farah Aideed and Ali Mahdi Mohamed on November 17 have been civilians.

Mogadishu, on the Indian Ocean coast, has been divided by Aideed's Habr Gedir clan and Ali Mahdi's Abgal clan.

Between them lies a no-man's land where the stench of death pervades streets that are a maze of smashed buildings and war debris.

Ironically, both leaders are from the same father-clan whose fighters ousted dictator Mohamed Siad Barre a year ago.

Ali Mahdi declared himself interim president in his place. Aideed bitterly resented this move and finally sought to reverse it by violence.

Now it has descended into tribal war, based on clan hatreds that date back centuries when fierce Somali nomads fought for control of scarce water and grazing for their camel herds.

The impoverished Horn of Africa nation has virtually collapsed as a state and is carved up into several tribal territories.

"There is no organised civil society left," said United Nations special envoy James Jonah after a recent visit to the city when he failed to broker a ceasefire.

"In such conditions the life of man is nasty, brutish and short and in the 20th century this cannot be tolerated."

Modern weapons have made the fighting more lethal than ever.

Gangs of youths, under the influence of the narcotic khat, race about the rubble-filled streets in trucks equipped with mortars, machine-guns and rocket-launchers taken from old jet fighters.

"There are three things a Somali loves: his gun, a camel and his horse," says Aideed. He admits that some gangs are out of control and hard to disarm.

A searing monsoon rain pelts the rubble-littered streets, interrupted by the sound of gunfire and mortar shells whining through the air before ploughing into buildings.

The telephone, electricity and water systems have completely broken down. Foreign embassies other than Sudan, Egypt and the Palestine Liberation Organisation left a year ago.

Both sides say they want a ceasefire, blaming the fighting on the other and refusing to end the shelling.

"Sometimes a whole family comes in, sometimes the parents are dead," says Abdirazak Hassan, a doctor at Benadir hospital.

On a quiet day Benadir receives 50 casualties, the figure rising to 200 when mortar bombardments are more intensive.

The town's three other hospitals -- all of them in Aideed's area of control -- have similar casualty numbers.

In Ali Mahdi's northern stronghold in Karaan district, clinics have been set up in bombed-out houses where amputations are carried out on the bare floor, often without anaesthetic.

Hundreds of thousands have fled the fighting and are living in shanty towns outside the city where they face starvation and disease.

"Most families have nothing to eat," Abdirazak Hassan says.

More than two months ago the U.N. estimated that 4.5 million Somalis were going hungry and that deaths would escalate unless security was restored to allow distribution of food aid.

But after the murders of an International Red Cross delegate in the city In December and a U.N. doctor in the northern port of Bossaso earlier this month, relief operations been curtailed.

Calls for an international peace-keeping force to be sent in to secure relief assistance and create a neutral zone around hospitals, the port and airport have been increasing since failure of the U.N. to bring the warring sides to a truce.

"Otherwise we might have to pull out," says SOS head Willy Huber.

Huber is one the few relief workers who have refused to leave the city but he fears operations will become impossible if the fighting continues.

"We would like to assist a U.N. intervention and would not be prejudiced against any country coming in to restore order," says Ali Mahdi.

However Aideed counters: "Foreign intervention will not solve the already complicated situation in Somalia, but will complicate it more. We are able to solve our own problems".

Political analysts say a peace-keeping force could not be sent in until a truce is in place. The chances of this appear remote.

"We will fight until the last one of us is dead," said one Somali youth.

© 1992 Reuters Limited

'A place, no longer a city, of complete madness' Insanity of life in Mogadishu

January 13, 1992 The Independent - London

Richard Dowden reports on the insanity of life in Somalia's dangerous capital and finds, at shell-rocked Digfer hospital, the 'inner circle of Mogadishu's hell'.

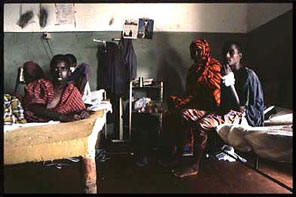

The smear of blood thickens as you walk towards the emergency casualty room at Digfer hospital. Lines of drops of blood converge on the front door and as you follow them they merge until your shoes stick to the floor.

In pools of blood men, women and children lie crammed together on the floors. Nurses set up intravenous drips for the worst cases, but already one or two have been covered with a blanket.

"Sometimes we have to leave cases with open fractures for three or four days - there are so many coming in," said Bill Moore, an American former Vietnam MASH doctor working with International Medical Corps. "I never saw anything like this in Vietnam. I never saw anything like this anywhere."

In the operating theatre the staff are mopping up yesterday's blood - they can only clean up once a day and did 38 operations on Saturday. There are 20 people on the floor of the casualty room. A woman lies moaning; a bullet has shattered her leg and another is lodged behind her ear. Her teenage daughter fans her while her smaller daughter, perhaps six or seven, looks on in bewilderment.

There are no painkillers here. Families live on the floor next to their injured relatives - the hospital has no food, and relatives have to feed, wash and tend patients and give them blood for transfusions. The sickly-sweet smell of blood hangs in the throat, mingled with something putrid.

The building shakes as another shell bursts near by. "Open the windows," shouts Dr Moore. "It'll only let in more flies," replies a colleague. "Better flies than flying glass," comes the reply. The dark, grimy hospital corridors are filling up with people sheltering as if from the rain.

That shell landed near the hospital gate. A few yards down the road is a T65 tank and a multiple rocket launcher. As we turn the corner, the tank fires straight into some houses.

Digfer hospital must be the inner circle of Mogadishu's hell. It is a place - no longer a city - of complete madness. At the airport in the afternoon a small Red Cross aircraft brings in emergency medical supplies. The airport is guarded by one clan, not involved in the war, but as the plane arrives a fight breaks out over who shall help to unload it. One man is screaming and pointing a gun at Red Cross officials. Others wrest the gun from him, everyone is shrieking, punching and waving their weapons. And they are all from one clan.

The war which has destroyed Mogadishu is between two sub-clans of the Hawiye. Somalia's other two main clans and their myriad sub-clans have not yet even begun to sort out their differences since Siad Barre was overthrown almost a year ago. All are armed with tanks, rockets and rifles.

It is as if a whole nation was committing genosuicide. Yesterday was the worst day so far - perhaps the only fact that the inhabitants of Mogadishu can agree upon. It began on Saturday afternoon after two quiet days - there was even talk of negotiations. People said the two warring sub-clans, the Habar Gedir and Abgal, had fought each other to a standstill. There were rumours that the two other sub-clans of the Hawiye, the Murasad and the Hawadle, were getting together to stop the fighting.

They were wrong. On Saturday afternoon the Murasad joined in, taking on the Habar Gedir in the west of the town. The artillery banged on all night and, as dawn broke yesterday, the fighting turned into a full-scale, house-to-house battle with tanks and anti-aircraft guns used horizontally. Parts of the city relatively untouched came under shellfire, sending people on to the streets in their hundreds as they fled.

There has been no electrical power for a year, but yesterday water went off and the fighting has stopped people getting to the only functioning market. "There will be mass starvation, that's for sure," said Dominik Stillhart, the representative of the International Committee of the Red Cross. When the fighting started the Red Cross was feeding 200,000 people. Mr Stillhart estimates that was a third of those who needed food. Now, 57 days on, things can only be worse.

Thousands have moved to the edge of Mogadishu, having fled their homes, which have been looted. They have only what they fled with, and wait to die huddled under trees. When the rain comes at the end of next month there will almost certainly be an outbreak of cholera. The battle for what was once Somalia, once Mogadishu, will become a war for food.

About 30 expatriates work on, mostly involved in supplying hospitals and helping the Somali medical staff who work, sometimes 24 hours a day and unpaid. The expatriates from the Red, Cross, Save the Children Fund and other aid agencies, live behind high walls in compounds protected by hi red gunmen. Even the Red Cross has dispensed with its usual rules and travels with armed guards. "There is no alternative," said Mr Stillhart. "The food, the medicines, everything needs protection, it is that or nothing."

The local security guidelines of the Save the Children Fund sum up the insanity of life in Mogadishu and the risk of sudden death from bandits or mad gunmen: "Do not wear a seatbelt - you may need to get out of the car suddenly... and if you are stopped and reach down to undo a seat belt it may be interpreted as a move for a gun."

Last night as dusk fell David Shearer, the Save the Children Fund representative, checked the compound: "The guards have prayed and cleaned their weapons so they have both options covered - let's hope for a quiet night."

© 1992 Independent Newspapers (UK) Limited . All rights reserved.

Chaos is king in Somalia land of civil war and not much else Series: GLOBAL VILLAGE

REENA SHAH January 12, 1992 St. Petersburg Times, 17A

If countries could win awards for allowing the random killing of thousands of civilians in the shortest time, I would nominate Somalia, whose government probably would not qualify for a prize in any nicer category.

Since November, about 20,000 Somalis have been killed. Some say it could be twice that number. Nobody is certain because hardly anyone who has the ear of the rest of the world is in Somalia. Even the United Nations pulled out of the capital, Mogadishu. It promised recently to resume some relief work, a dangerous proposition since Somali factions also are shooting aid workers - anyone who interferes with target practice on civilians.

There isn't much to fight over. Somalia is a poor, nomadic country stuck like a Band-Aid on the eastern snout of Africa. Its wealth is in the goats and camels its people raise; the country exports leather to Italy and live animals to Saudi Arabia.

And compared to other African countries that are composed of hundreds of mutually suspicious tribes, Somalia is dominated by seven clans and shouldn't be engaged in a bloodbath. Yet Somalis are killing each other by the thousands. The two warring factions represent rival groups of the Hawiye clan. Each wants power by terrorizing people rather than winning their confidence through elections. Both sides have armed their supporters, including young boys, with guns and grenades.

Somali civilians literally are held hostage in their country. Some who are fortunate have been able to flee as refugees to neighboring Ethiopia, which also is famine-stricken but at least is free of war. Those who remain are afraid to accept the little food sporadically available from aid workers. Soldiers shoot people who have food.

One faction is headed by Ali Mahdi, who took charge of the government when Mohammed Siad Barre, the country's military dictator for 21 years, was toppled early last year. The other is headed by Gen. Mohammed Aideed.

Blame some of this on Somalia's history.

When Africa was colonized in the 19th century, Britain ruled northern Somalia and Italy ruled the south. The two parts were joined when Somalia became an independent country in 1960 but are still suspicious of each other. Aideed opposes Ali Mahdi because he thinks he is pro-Italian. The formerly British north doesn't support Mahdi. It seceded last year and now calls itself Somaliland. It has yet to be recognized, but it is peaceful. So far.

Somalia's clans always have squabbled over pasture land, over water rights, over power. When Siad Barre, the former dictator, seized power in 1969, he undertook a disastrous experiment with socialism. Then, when the Soviets appeared to favor neighboring Ethiopia with more weapons, Siad Barre became a capitalist who wooed and won U.S. support. For the last 10 years, Somalia was one of the largest recipients of U.S. military aid in Africa. When the Cold War ended, U.S. aid dried up. The reason given was that Somalia's government had been overthrown violently and its human-rights record was appalling.

The United States sends some emergency shipments of food. The Cold War may be over, but its ghost haunts Somalia. U.S. and Soviet guns are sniping at and killing the country's own people.

© (Copyright 1992)

In Somali Capital, Shrapnel Reigns; Civilians Pay Heavy Price In Artillery Duel for Power

Keith B. Richburg Washington Post Foreign Service January 11, 1992 The Washington Post

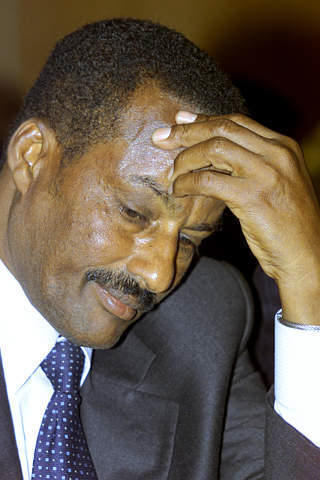

Aideed: We are seeking to arrest Ali Mahdi.

Ali Mahdi: Aideed is no different from Siad Barre.

Measured against the daily violence in this battle-scarred capital, Wednesday was a quiet day at Benadir hospital. One child arrived with his fingers blown off by a stray grenade. Two small children were burned over most of their bodies in an explosion. There was the usual assortment of torn abdomens from shrapnel.

The shelling was light that day, with only a few rounds of artillery exchanged around noon. Hospitals on both sides of the divided city reported fewer than the average number of wounded. In many ways, there was an eerie air of normality, with a few street vendors selling cigarettes, mangoes, bananas, even some meat.

The calm, however, was only a momentary respite from the orgy of brutality that has turned this once-quaint seaside capital of white villas into an urban nightmare of war, lawlessness and impending famine. People here talk of the shelling - now in its eighth week - like people elsewhere might discuss the rain: not too heavy today, but likely to pick up again tomorrow. No one thinks it will end anytime soon.

Two men are largely responsible for the death and destruction being rained on this city. One claims to be president, but he has no real power, he is confined to a few blocks of the city, and the country he supposedly rules, Somalia, has in many ways ceased to exist; the other is an army general seeking to oust him.

They are similar in many ways. Both claim to represent democracy and say they are trying to prevent Somalia from returning to the dark days of dictatorship. Both are stubborn and uncompromising. And since Nov. 17, when their war of words erupted into a war of artillery, the entire city has been caught in the middle.

On one side is Ali Mahdi Mohamed, the nominal president. In a small room laid out with a red Persian carpet, he described in an interview Wednesday the current state of chaos in the capital. His voice was being drowned out by the heavy thud of artillery shells outside, first in the distance, then growing closer.

"There is no economic entity prevailing in this country," he said over the explosions. "Everything has collapsed. . . . Anarchy is prevailing also. With no police or military, it is very difficult to run the country." His last sentence was punctuated by a burst of automatic weapons fire from just outside the window.

An aide told the president's visitors to relax. The villa was safe, he said, for the time being. Besides, at least some of the explosions were caused by outgoing artillery shells, headed across town. The president himself said he was not afraid. "As a Muslim," he said, "I know my fate is predestined."

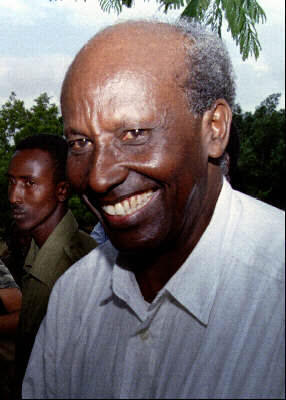

On the other side of the city, across barricades of old tires and twisted metal - and a barren stretch of highway known locally as No Man's Land - the president's antagonist also entertained visitors, in a more spacious and heavily fortified villa that had the official air of a military command center. In a relaxed, soft-spoken voice, Gen. Mohamed Farah Aideed offered his explanation for the high level of violence in a city where it seems every male adult and child is armed.

"Traditionally, Somali people love three things," he said. "One is keeping small arms with them. Another is their camel. And finally their horse. Somalis love horses." He laughed at his own humor, and continued. Somalia, he said, did not need outside intervention to solve this ongoing conflict because he, the general, was "already taking action to solve our problem."

"We prefer to solve our own problems," he said.

Aideed sees Ali Mahdi as the "problem," and his solution has been a relentless artillery barrage on the northern section of the city called Karaan, where the president is clinging precariously to his position. And Ali Mahdi has responded in turn, shelling the areas controlled by the general - and hitting anything in the vicinity of the general's headquarters.

This week, the crowded Benadir hospital was hit, for which Ali Mahdi offered an apology. "Maybe we missed and killed some civilians," he said in the interview. "I'm very sorry about that."

Their personal duel has been brutally played out in the streets of the capital. They have carved up the city into warring camps. Artillery shells have wrecked streets and buildings. Burned-out and mangled cars litter largely empty highways. In the absence of any kind of authority, armed militias have taken to roaming the streets in jeeps outfitted with rockets, mortars and antiaircraft guns.

There has been no electricity in the city since anyone can remember, and the highway is marked by holes from which scavengers have removed underground cables. Water and fuel are scarce. An estimated 300,000 people have fled the capital to outlying areas to escape the carnage.

The city is also on the edge of famine, according to the few relief workers still here. Although some food was being sold by street vendors Wednesday, the aid workers said most people have no means to buy the few goods still being brought in. The last major relief agency foodstocks to arrive were reportedly looted from the warehouse before they could be distributed, and aid workers said bringing in food now without some kind of organized system to distribute it would lead to riots.

A relief worker for the international aid agency SOS-Kinderdorf said he was afraid he might lose his entire project in Mogadishu - a maternity care clinic and adjacent pediatrics clinic - because people were getting so desperate for food in the capital that he could not guarantee the safety of his facility from looters for much longer. In one incident already, a hungry woman with a gun came to the clinic gates demanding food.

Workers at the pediatrics clinic, in the area controlled by Aideed, said they can gauge the extent of the day's artillery barrages by the number of malnourished children who show up at the gates. When the shelling is light, the clinic receives about 450 new children every day, they said. During the heaviest shelling, in the week before Christmas, the figure dropped to about 60 a day. The number is back up to about 200 a day, workers said, reflecting a slight lull in the shelling.

The human toll of the continuing violence can be seen at the city's hospitals and makeshift clinics, on both sides of the capital. So far, the war has left an estimated 5,000 people dead and twice as many wounded. Hundreds of victims, mostly women and children hit by shrapnel, take up most available bed and floor space each day. The city is suffering from an acute shortage of even the most basic medical supplies.

At Benadir hospital on the side of the city controlled by Aideed, about 50 people each day are treated for gunshot and shrapnel wounds, some of which were caused by bombs and grenades that litter the streets, said Omar Bile, a doctor. On Wednesday afternoon, two small boys were being treated for burns over their entire bodies after some kind of incendiary device they were playing near exploded. As they were being treated, two young girls, both with amputated arms, looked on curiously.

A makeshift hospital set up in a villa on the Ali Mahdi side has treated about 3,575 people since Nov. 17. Prof. Abdullahi Sheik Hussein, dean of medicine of the Somali National University, said the hospital receives about 40 victims on a day of light shelling, and about 100-a-day when the fighting is most intense.

"War should be between militaries," he said. "Shelling only hurts civilians. That's not war."

Like virtually all Somalis, the doctor has chosen sides in this conflict. He called Aideed "a psychopath" who would establish another military dictatorship like that of former U.S.-backed ruler Mohamed Siad Barre, who was ousted a year ago. "We have kicked out one general," Hussein said, referring to Siad Barre. "We don't want to put another dictator in. . . . This is a battle between dictatorship and democracy."

In the current tragedy of Mogadishu, it is difficult to tell between the president and the general who is the democrat and who the would-be dictator.

Ali Mahdi is 52, and Aideed 56. Both come from the same Hawiye clan, and claim the same political grouping, the United Somali Congress. Ali Mahdi is a businessman by profession, who ran a hotel (now destroyed) in the capital during the Siad Barre regime. Aideed is an Italian-trained officer who once served as ambassador to India.

Ali Mahdi claims he is the rightful ruler, since a group of clans meeting in Djibouti selected him interim president after Siad Barre fled the capital. Aideed, he said, "is no different from Siad Barre."

"There are two forces," Ali Mahdi said, "forces that want democracy and peace and free elections, and forces that want a return to military dictatorship." He called himself a reluctant ruler, a businessman who would just as soon step aside because "I don't like to be president."

Aideed called Ali Mahdi a "criminal" and said he is corrupt. He said he launched his campaign to oust Ali Mahdi because he considers him an illegitimate ruler who was enriching himself and his cronies. "They have committed a lot of crimes," Aideed said of Ali Mahdi and his administration. "We are seeking to arrest him."

Both men say they are ready to accept a cease-fire, and each accuses the other of rejecting the terms. Ali Mahdi said he will accept a United Nations peace-keeping force, since, in his view, such a force would help prop up his own, legally installed administration. Aideed rejects foreign intervention, saying he has the "problem" well in hand.

It is difficult to determine which side is winning, since they both claim to control the major portion of the city. From a one-day visit, however, it appeared that Aideed's forces controlled most of the capital, including the site of the now destroyed American Embassy compound, most hospitals and the international airport. Ali Mahdi appears confined to the Karaan section of the northeast.

Most of the few flights into and out of Mogadishu land on the Aideed side under his protection. As Nairobi-based journalists were leaving the city at dusk after their day-long visit, their van was met at the airport gate by a sentry with an automatic rifle strapped around his shoulder.

The sentry was a boy of no more than 10.

© (Copyright 1992)

SOMALI GUNMEN DRIVE THROUGH THE STREETS OF THE CAPITAL MOGADISHU

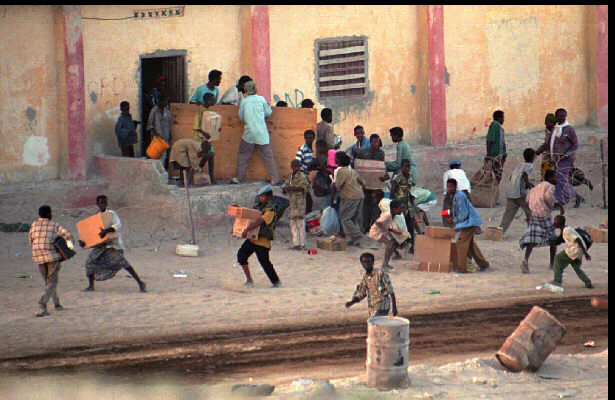

Somalis loot U.N. barracks near the Mogadishu port

|