|

Marauding Saracen |

|

A M E R C E N A R Y B Y A N Y O T H E R N A M E

D E C E M B E R 2 7, 2 0 1 0

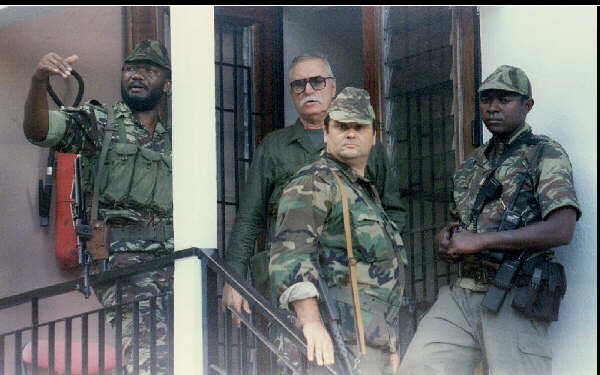

French mercenary Bob Denard (with glasses) and Army Capitan Combo Ayouba (L) direct operations October 4, 1995 from inside the Kandami Barracks, where Cormoros President Mohamad Said Djohar is being held hostage by veteran French mercenary Bob Denard in a coup d'etat September 28 in the Indian Ocean archipelago of Comoros.

Marauding Saracen A Mercenary by Any Other Name Biyokulule Online December 27, 2010

This paper discusses the recently promoted view that government counter-insurgence campaign should rather be conducted by self-interested quasi-mercenaries, instead of AMISOM forces. It is not entirely clear that the fez-wearing sheikhs have learned from the unfortunate Somali experiences. There are reports circulating in the Somali media that states Villa Somalia’s final decision to hire foreign security firm. The chitchats coming out from the bunker walls of Villa Somalia are also rising loudly and are in favour of bringing quasi-mercenaries into Somalia, although Villa Somalia publicly denounces it.

Despite the almost universally unanimous distaste for quasi-mercenaries, the fez-wearing sheikhs who are now playing political midwife to Somalia assume that foreign private security actors are cheaper and more effective than UN or AMISOM forces.

Historical Perspective

A traditional argument on the issue of mercenaries in general is provided in Niccolo Machiavelli's book, The Prince. Machiavelli stated that good laws are not possible without good arms and that, where there are good arms, good laws inevitably follow. However, the conclusion of Machiavelli's discussion on military forces was that “If a prince bases the defence of his state on mercenaries he will never achieve stability or security.” The philosopher inscribed on his notebook:

… mercenaries are disunited, thirsty for power, undisciplined, and disloyal; they are brave among their friends and cowards before the enemy; they have no fear of God, they do not keep faith with their fellow men; they avoid defeat just so long as they avoid battle; in peacetime you are despoiled by them, and in wartime by the enemy. The reason for all this is that there is no loyalty or inducement to keep them on the field apart from the little they are paid, and this is not enough to make them want to die for you. They are only too ready to serve in your army when you are not at war; but when war comes they either desert or disperse … [1]

Unbelievably, we are today experiencing the apex of mercenary-dependence. The world’s most powerful country, the United States of America, “sought to keep American soldiers and officers away from legal accountability by using suspect security firms, on the pretext of protecting US Army personnel and officials.”

Subsequently, the recent American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have been characterized by the reliance of large non-American private security personnel, under contract with the US administration. According to the Private Security Company Association of Iraq, “there are more than 180 such companies in operation that now employ 70,000 armed private security contractors in the country, and that number is only growing.”

Pointing the finger to former US President, George W. Bush, who preferred to channel funds to private security actors, American writer, Ralph Peters, blatantly said “sadistic, too-often-murderous conduct of thousands of private security contractors - our contemporary euphemism for mercenaries – not only shattered critical relationships between our troops and the local population but also shamed our country.”

Seeking redemption

Since Sheikh Sharif’s Administration failed to win over hearts and minds of enough local troops, it decided to outsource its security department. And since local soldiers that are loyal to Villa Somalia are in short supply, foreign private security firms want to fill the gap and have free hand to create their marauding local militia, as it is happening now in Afghanistan.

Last November however, “Afghanistan's government has ordered private security firms to disband and leave the country amid anger among ordinary Afghans who regard them as private militias acting above the law”. [AFP November 09, 2010]. Unfortunately, these soldiers of fortune may have now turned their eyes to the ongoing Somali civil war, which could prove to be a pot of gold.

Incidentally, Somalia is also contemplating the idea of relying on private firms that provide security services in an unstable environment. In fact, not since late 1980s has there been such a reliance on private security contractors to carry out tasks directly affecting the success of military engagements.

This year, Saracen International represented itself to Villa Somalia as a “private security” company, the current euphemism for mercenaries, which translates as contractors for freelance vigilance.

In 1996, the Human Rights Watch report names Saracen International, as suspected Executive Outcomes front company. And Executive Outcomes is far more than a private security firm; it is a group of mercenaries that employs intelligence experts and a range of code-named “technical” staff. Within a very short period of time, it had generated over dozen subsidiary companies throughout sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.

Moreover, documents that dated back to March 1995 showed a string of security companies (specializing in VIP protection), including Saracen International, set up as a front for Executive Outcomes in providing logistical supplies to United Nations-related organizations.

CIA’s anti-terror mercenaries in Mogadishu

It was just four years ago, when the scandal of US hired warlords was uncovered. Washington clandestinely helped warlord Mohamed Farah Qanyare to form his Murasade clan militias as the core of a CIA-created mercenary force (called the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism in Somalia) to confront the then rising tide of Sheikh Sharif’s Union of Islamic Courts (UIC) in Mogadishu. For his private pursuit of thousands of dollar bounty on any Somali with rags around their heads, Qanyare instructed his militia to emulate Rambo-style hero and hunt down religious men in any teashop in Mogadishu.

As for the CIA’s anti-terror mercenaries in Mogadishu, Qanyare’s militia were known for their brutality and indiscriminate kidnappings and assassinations with all religious men, moderates or extremists. In short, the operation of the Somalis on the CIA payroll resembles the job of armed mafias that know only the language of killing. However, the ill-advised US operations in Somalia ended up in swelling the ranks of UIC.

Matt Bryden, a security analyst who has written extensively on Somalia’s Islamist insurgency, concluded that the creation of a CIA-directed mercenary force in Mogadishu was a stupid idea. “It actually strengthened the hand of the Islamists and helped trigger the crisis we’re in today."

This article does not object the moral justification for Just War tradition and acknowledges that there is nothing inherently objectionable about “private security” tasks in general. However, it simply exposes the most obvious fallacies of modern private security tasks in war-torn regions of the world – one that appeals to the importance of enabling just defensive killings. As senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies, Sabelo Gumedze, noted that there is a fine line between private security and private military; and as often happens, security companies involve in military services.

Lastly, Roobdoon Forum forwards to its readers excerpts of news articles that relate to the transformation of quasi-mercenary firms into “private security” contractors. We hope that these selections will have a lasting impact on you, regarding the underworld of “private security” actors.

Reference

[1] See Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, translated with an introduction by George Bull (Harmondsworth, London, I96I), pp. 77-78.

Roobdoon Forum Toronto, Canada

Analysis Soldiers of Fortune by Christine Mungai December 27, 2010

Nairobi, Dec 27, 2010 (The East African/All Africa Global Media ) -- Events playing out in Somalia in the past one month almost look like a sequel to Black Hawk Down, the harrowing tale of how an ill-conceived mission by an elite team of American special forces went bad.

It is 18 years since America's last soldier left Somalia. Africa has finally agreed to take care of the mess in the Horn of Africa in a country that has been in the grip of a murderous terrorist group whose leadership and rank and file is filled with child soldiers and teenagers.

Uganda and Burundi are the only countries currently contributing troops to a peacekeeping mission in a conflict that has been made intractable by both internal politics and warlord benefiting from the war economy, and regional power interests.

Al Shabaab, the dominant rebel militia now routinely threatens global sea lanes and a crucial choke point through which 70 per cent of all global oil exports pass.

It is forging important links with Al Qaeda, the global terror franchise.

So far, it has successfully staged two foreign attacks in Kampala and Nairobi.

In the meantime, the balkanisation of Somalia is gathering pace with the establishment of Somaliland, Puntland, and soon Jubaland as peaceful, semi-automous enclaves that now seek international recognition as independent states.

US President Barack Obama has also recently unveiled his much awaited "Duo-Track" Somalia policy dubbed that seeks to support both the feeble and deeply corrupt Transitional Federal Government (TFG) whose mandate is expiring in July 2011, and the semi-autonous states that want to break free.

This is the same solution Kenya has been pushing with its Jubaland Initiative.

It is in this context that a former special adviser on war crimes to former president George W. Bush, Pierre Prosper, and a former CIA deputy station chief in Mogadishu, Michael Shanklin have linked up with President Yoweri Museveni's younger brother, who is also a retired Uganda general (Caleb Akwandanaho, alias Salim Saleh).

Mr Saleh is an investor in Saracen International, a private military company outfit based in Uganda.

There is even an "angel investor" rumoured to be a mysterious Middle East government that is funding the whole operation.

Their plan is to do what the armies from the world's only superpower and from the AU have failed to do: Empower the semi-autonomous state of Puntland to set up a 1,000 man commando unit to fight off pirates and secure its monopoly of the use of violence throughout its territory.

The plan will also include training a presidential guard for the TFG. If these two pilot projects work, there is a possibility of scaling their operation throughout Somalia.

According to security experts, the plan on paper could work, but in reality, a lot could go terribly wrong sparking an even deadlier wave of violence. These are the major worries.

First, the involvement of a private military company (PMC) -- let alone one associated with the brother of a president from the country contributing most troops -- was not sanctioned by the AU.

It may make member states uncomfortable, and it may enrage some like Somaliland which now feels threatened by its neighbour Puntland, and it may enrage Al Shaabab and the Somali populace which will interpret Salim Saleh's and Uganda's presence in their country as seeking to profit from their war.

The EastAfrican has obtained confidential information to the effect that Saracen International started the training in Puntland without the approval from the AU, making its activities controversially parallel to the mandate of the AU Mission to Somalia, Amisom.

Second, these developments also raise the question of how the UN and the AU sponsored peacekeeping mission will co-exist with private military companies.

Third, and perhaps the most worrying, is the confluence of global energy politics, religion and a corporate army in Somalia in an already volatile conflict.

Puntland is rich in oil and natural gas, and it is speculated that the entry of Saracen International is in return for concessions in oil exploration and extraction.

E.J. Hogendoorn, a Nairobi-based analyst with the International Crisis Group told the Associated Press, "We don't know if this unknown entity is operating in the interests of Somalis or their own self-interest. If it's a company, there has to be a quid pro quo in terms of [oil and gas] concessions. If it's a government, they are interested in changing the balance of power."

With the mandate of the Transitional Federal Government ending in July 2011, the emergence of an armed militia in Somalia is a source of concern for the stability of the Horn of Africa.

The combination of a weak state, valuable natural resources, and a for-profit military corporation is a scenario that has played out before on the African continent with devastating consequences, and history threatens to repeat itself in Puntland.

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, private military companies and defence contractors have played a growing role in the support of state armed forces, and in multilateral reconstruction strategies, such as in present-day Iraq.

These types of firms are also critical in raising and maintaining levels of security in unstable but economically strategic areas of the world.

Many states that had previously benefited from military aid found themselves in a precarious security situation at the end of the Cold War, requiring them to use PMCs to support their armed forces.

These contracts have historically been financed by the often controversial extraction of natural resources.

Mercenaries, PMCs, which?

There is a thin line between PMCs and mercenaries. Ever since men have waged wars, there have always been soldiers of fortune willing to sell their services.

Like piracy, the mercenary ethos resonates with an aura adventure, mystery, and danger, appearing frequently in popular culture, where they are often referred to as profiteers, adventurers, filibusters, gunslingers or knights-errant.

These security agents today prefer to be known as private military corporations, private military firms, private security providers or military service providers.

These companies refer to their business as the private military industry, in order to avoid the negative stigma often associated with the word mercenaries.

In the 20th century, mercenaries and PMCs widely involved in conflicts in Africa.

In some cases, their involvement had brought about a swift end to civil wars by comprehensively defeating rebel forces.

In 1960, when Katanga state declared its independence from the Congo, loosely organised bands of mercenary commandos illegally attacked UN peacekeeping troops.

This forced the Security Council to adopt the use of force by UN Security Council Resolution 161, and to request an immediate evacuation of all foreign belligerents.

Few mercenaries left the Congo, and most remained fighting with the Katanga secessionists.

The impact of mercenaries in the Congo has continued to date, where private military companies, that also double up as mining and extraction outfits or work in conjunction with them, continue fighting to secure natural resources.

The lack of trained troops, effective logistics and international support has weakened the ability of Monuc to carry out its mandate.

Conceivably, this absence of effective international action may drive the private sector to institute a private peacekeeping mission, backed by mining firms, in order to protect their investments in the country.

Executive Outcomes (EO), a now-defunct South African PMC, is notable on the continent for its direct military involvement in Angola and Sierra Leone.

Executive Outcomes initially trained and later fought on behalf of the Angolan government against rebel movement Unita, after Unita refused to accept Angola's election results in 1992.

The company was accused by the South African media of attempting to assassinate Unita rebel leader Jonas Savimbi, and as a result, EO found itself under constant Unita attack.

EO was then officially recognised by the Angolan Armed Forces (FAA) and subsequently awarded a contract to train the FAA.

In a short space of time, Unita was defeated on the battlefield and sued for peace. The Angolan government, under pressure from the UN and the US, was forced to terminate EO's contract. EO was replaced by a UN peacekeeping force.

In 1995, following the publicity EO received in Angola, the company was contracted by the government of Sierra Leone for $15 million to contain rebels of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), who controlled the natural resources of the country and were advancing on the capital, Freetown.

Within months of entering the conflict, the company had pushed back the RUF, regained control of the diamond fields, and forced a negotiated peace.

Government saviour

In both Angola and Sierra Leone, EO is credited with rescuing legitimate governments from destabilising forces.

In Angola, this led to a ceasefire and the Lusaka Protocol, which ended the Angolan civil war -- albeit only for a few years.

The company was notable for its ability to provide all aspects of a highly-trained modern army to the less professional government forces of Sierra Leone and Angola.

For instance, in Sierra Leone, Executive Outcomes fielded not only professional fighting men, but armour and support aircraft.

Interestingly, Executive Outcomes had contracts with multinationals such as De Beers, Chevron, Rio Tinto Zinc and Texaco.

The founder of EO, Tony Buckingham, was also the founder and director of mining and extraction firm Branch Heritage, which was sold to Diamond Works in 1996.

Branch Heritage acquired concessions to extract diamonds in Sierra Leone, and also paid the bill for EO's interventions in that country.

EO was not the first PMC to involve itself in the Sierra Leonean conflict.

It was preceded by Gurkha Security Guards, and would be succeeded by Sandline International.

Sandline billed itself as a PMC offering military training, "operational support" (equipment and arms procurement and limited direct military activity), intelligence gathering, and public relations services to governments and corporations.

Sandline was contracted by ousted Sierra Leonean president Ahmed Tejan Kabbah and in Liberia in 2003 in a rebel attempt to evict the then-president Charles Taylor near the end of the civil war.

Sandline ceased all operations on April 16, 2004. On the company's website, a statement explaining the closure of the company is given: "The general lack of governmental support for private military companies willing to help end armed conflicts in places like Africa, in the absence of effective international intervention, is the reason for this decision. Without such support the ability of Sandline to make a positive difference in countries where there is widespread brutality and genocidal behaviour is materially diminished."

It has been rumoured that some of Sandline's personnel are now part of Aegis Defence Services, a British PMC active in Afghanistan and Iraq.

These apparent successes of PMCs promote the concept that these companies can achieve peace faster and cheaper than UN peacekeeping missions.

In retrospect, however, the presence of PMCs actually poured more weapons into conflict zones, weakened the economy and created a base for further conflict, as was the case with EO's involvement in Angola.

Perhaps the most notorious of all PMCs is Blackwater USA, which changed its name to Blackwater Worldwide, and is now known as Xe Services.

The company was formed in 1997 by Erik Prince in North Carolina.

In 2003, Blackwater attained its first high-profile contract when it received a $21 million no-bid contract for guarding the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, L. Paul Bremer.

Since June 2004, Blackwater has been paid more than $320 million out of a $1 billion, five-year State Department budget for the Worldwide Personal Protective Service, which protects U.S. officials and some foreign officials in conflict zones.

The company has been implicated in several human-rights abuses in Iraq.

The Iraq War documents leak posted on WikiLeaks showed that Blackwater employees had committed serious abuses in Iraq, including killing civilians.

Altogether, the documents reveal fourteen separate shooting incidents involving Blackwater forces, which resulted in the deaths of ten civilians and the wounding of seven others, not including the Nisoor Square massacre in Baghdad that killed seventeen civilians.

A third of the shootings occurred while Blackwater forces were guarding US diplomats.

Court documents made public reveal that Blackwater/Xe violated US federal law hundreds of times according to allegations by the federal government.

In August 2010, the company agreed to pay a $42 million fine to settle allegations that it unlawfully provided armaments, military equipment and know-how overseas.

The settlement and fine conclude a U.S. State Department investigation that began in 2007.

Most of the 288 violations of export control laws involved violations of US arms control laws, that is Blackwater/Xe providing military or security training to foreign nationals or failing to vet adequately the backgrounds of those it was training.

The implications of Saracen International's involvement in Somalia are therefore far-reaching.

It has often been presented that PMCs are cheaper and more efficient than UN peacekeeping operations, and proponents of this idea give Angola and Sierra Leone as examples.

However, the mandate of PMCs in those two conflicts was to destroy rebel opposition, and not to involve themselves in the peace process.

The mandate of UN peacekeeping operations, and indeed Amisom in Somalia, is not to conduct war or destroy an enemy.

The respect of national sovereignty, the need of self determination of citizens and the promotion of international peace and security are difficult to put together in a coherent manner in peacekeeping operations.

PMCs are not faced with these dilemmas, however, and this is the reason why, at face-value, they seem to be more efficient than a UN mission.

These companies are only effective in the short-term as they do not address the core situations, but only temporarily delay the resumption of combat.

Accountability of PMCs is also put in question; these companies are ideally accountable to their national judiciary systems, but these are often ineffective abroad.

No official body monitors their rules of engagement as they often operate in weak states which are unable to provide a firm judicial framework to regulate PMC activities.

The situation in Somalia, therefore, needs to be closely monitored.

Peacekeeping operations, including "anti-piracy" missions should not be left in the hands of the private sector, especially in an environment as fragile as Somalia's.

© 2010 AllAfrica, All Rights Reserved

Corporate Dogs of War Who Grow Fat Amid the Anarchy of Africa By Khareen Pech and David Beresford The Observer January 19, 1997

Scourges or saviours of a troubled continent? Khareen Pech and David Beresford uncover British intelligence documents which point to an expanding role for South Africa's highly paid mercenaries

THERE is, some say, a new imperialism at work in Africa. But it knows no ideology beyond the laws of profit and feeds on the conflicts of a troubled continent. According to others, it brings order. It provides a pan-African peace-keeping force of a kind the international community has promised but failed to deliver.

Executive Outcomes has fought many battles in Africa with guns, bombs, gunships and jet fighters. Today the controversial company that has brought a new dimension to the concept of the 'corporate state' - mustering what is arguably the world's first fully equipped corporate army - is again fighting for survival, this time in the arena of public opinion.

It is six years since the name of Executive Outcomes began to be heard in Africa. Nowadays it tends to feature whenever and wherever there is a new outbreak of the warfare to which this weary continent has become so accustomed. As Zaire threatens to implode, there is intense speculation (denied by the company) that its mercenaries are moving in to shore up the crumbling rule of President Mobutu.

The origins of Executive Outcomes are shrouded in some mystery, which is hardly surprising when one considers the circumstances of its creation and the characters involved.

A 'UK Eyes Alpha' ('top secret') British intelligence report records that 'Executive Outcomes was registered in the UK on September 1993 by Anthony (Tony) Buckingham, a British businessman, and Simon Mann, a former British officer'.

Buckingham and Mann are central figures in the Executive Outcomes saga, although Buckingham denies any 'corporate link'. A veteran of the SAS and a close friend and business associate of former Liberal Party leader Sir David Steel, Buckingham is chief executive of Heritage Oil and Gas, which has drilling interests in Angola and other parts of the world.

Heritage - originally British, now incorporated in the Bahamas - was also linked with a Canadian oil corporation, Ranger Oil.

Mann, a former troop commander in 22 SAS specialising in intelligence, has seen service in Cyprus, Germany, Norway, Canada, Central America and Northern Ireland. As an expert in intelligence systems, he has worked in Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and Nigeria, among other countries.

It was in 1993 that Buckingham and Mann first met Eeben Barlow, a former officer in the South African Defence Force. Barlow had served in some of the most notorious units in the South African military, including the Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB) - an apartheid-era state-run assassination network organised on corporate lines.

According to former colleagues, he handled operations in Europe, where he was able to develop contacts within both Western and Eastern European secret service s and helped to facilitate South Africa's sanctions-busting operations.

One of the centres of the oil industry in Angola is the town of Soyo, which was under the control of rebel Unita forces in the early 1990s. In January 1993, Buckingham and Mann commissioned Barlow to recruit a force of South Africans with combat experience in the former Portuguese colony to seize the town. A force of fewer than 100 men succeeded. But Unita quickly recaptured it after the South Africans had left. Luanda then asked Ranger and Heritage to hire a larger force in exchange for oil concessions.

According to the British intelligence document, Ranger allocated $30m (#19m) for the operation and placed the contract with Buckingham and Mann. They in turn appointed Barlow and Lafras Luitingh - a former colleague of Barlow's in the CCB, who had led the first attack on Soyo - to recruit and command about 500 men, most of them former members of the South African Defence Force.

Recruitment in South Africa appears to have been, if not facilitated, at least winked at by senior leaders of the African National Congress who - as the British report puts it - believed 'it would remove personnel who might have had a destabilising effect on the forthcoming multiracial elections'.

The story of the success of Executive Outcomes in Angola is now well known. With sophisticated weaponry - such as devastating fuel-air bombs obtained from a Russian supplier - the mercenary force effectively turned the course of the civil war. From there they moved on to Sierra Leone, shoring up the regime of Valentine Strasser against the Revolutionary United Front of Foday Sankoh, which was on the point of seizing Freetown when Executive Outcomes intervened.

Since those days Executive Outcomes's tentacles have spread over the continent with astonishing speed. The Observer has established that the company has a substantial presence in Kenya, where it has had business dealings with Raymond Moi, son of President Daniel arap Moi.

It has been reported that Executive Outcomes has had links with more than 30 countries, mostly in Africa. (It is also believed to have ties with Malaysia and South Korea.)

The Executive Outcomes mercenaries are not simply 'guns for hire'. They are the advance guard for major business interests engaged in a latter-day scramble for the mineral wealth of Africa. A hint of the breadth of their operations is provided by an office block in Chelsea. On the second floor of a modern, glass-fronted building at 535 King's Road, known as 'Plaza 107', a single receptionist handles incoming calls to more than 18 different companies. Buckingham, Mann and others run businesses which include international oil, gold and diamond-mining ventures, a chartered accountancy practice, an airline, foreign security services and offshore financial management services.

The Observer has a list of company and staff names dated to September 1994. Included are Executive Outcomes Ltd, Heritage Oil and Gas and a management services company called Plaza 107 Ltd, which heads the list in bold type. Other company names include Ibis Air International, Branch International Ltd, Branch Mining Ltd and Capricorn Systems Ltd. Among the list of directors and staff are Buckingham, Mann and Sir David Steel and the South African director of Ibis Air, Crause Steyl.

It is suspected that the name Capricorn originates with the Capricorn Africa Society, established by the eccentric military hero who founded the SAS, Sir David Stirling - who was himself involved in mercenary operations before his death in 1990, aged 74.

Another company which took the name was Capricorn Air. When the mercenaries first flew into Angola in 1993, on two Beechcraft light aircraft that operated out of Lanseria, a small airport outside Johannesburg, it was by courtesy of Capricorn.

Later registered as Ibis Air in both Angola and South Africa, this has effectively developed into a substantial air force. It reportedly includes a fleet of Boeing 727s, at least two MI-17 helicopters, two 'Hind' MI-24 gunships, several small fixed-wings - one of which has surveillance capabilities - at least two jet fighters and several private jets.

After an accident at Lanseria involving one of the Boeings, Ibis moved operations to facilities provided by Simera, an aviation division of the South African state arms development and procurement firm Denel, which as the Atlas Aircraft Corporation used to build the country's combat aircraft. For two years, Denel has stored and maintained the aircraft used to transport Executive Outcomes' hired forces into African war zones.

Company documents show that the airline flies between African capitals including Luanda, Freetown and Nairobi, and the island of Malta - where it is thought Ibis is based. Both Buckingham and Mann are directors of Ibis. Luitingh and several other Executive Outcomes associates are involved in running the airline.

Branch International is believed to be the holding corporation for a string of subsidiaries and associated companies engaged in the hunt for oil, gold and diamonds among other gems and minerals.

IN SOUTH AFRICA, Plaza 107 is mirrored by Strategic Resources Corporation, based in a suburban house in the affluent suburb of Lynnwood, Pretoria.

Bank documents dated March 1995 showed this to be the holding corporation for another string of companies including Saracen, a security company specialising in 'VIP protection, strategic point protection and business security protection', Falconer Systems, set up as a front for Executive Outcomes in providing logistical supples to 'United Nations-related organisations', and Bridge International, which specialises in construction and civil engineering.

The British intelligence document says Executive Outcomes 'is acquiring a wide reputation in sub-Saharan Africa for reliability and efficiency', with a particular appeal to 'smaller countries desperate for rapid assistance'. By contrast, the document says that UN operations are cumbersome and slow and that the Organisation for African Unity is seen as a talking shop. There 'is every likelihood' that the company's services, already extending into imports and exports and administration, 'will continue increasingly to be sought'.

But the document warns that such widespread activities are a cause for concern because the company is able to barter its services 'for large shares of an employing nation's natural resources and commodities'.

It continues: 'On present showing, Executive Outcomes will become ever richer and more potent, capable of exercising real power, even to the extent of keeping military regimes in being. If it continues to expand at the present rate, its influence in sub-Saharan Africa could become crucial.'

South Africa's ANC government is belatedly moving to try to throttle it. Last month the national conventional arms control committee announced it would ask the Cape Town parliament to rush through legislation designed to curtail the involvement of South Africans in mercenary activities by subjecting the sale of military or intelligence services to the same licensing process as military hardware.

Barlow makes light of the proposed legislation: 'We are quite happy about it.' He said the legislation is 'not aimed at us and we have no fears for that'. He added: 'We are not going to help anyone that is not a legitimate government or which poses a threat to South Africa, or that is involved in activities really frowned upon by the outside world. We have had a major impact on Africa. We have brought peace to two countries almost totally destroyed by civil wars.'

The major powers could still squash Executive Outcomes. But for them Africa is a plague on the conscience and a trap for the unwary. They are content to leave its murkier transactions to those enjoying the limited liability of the corporate world.

© 1997

Opinion War and Commerce Link Revealed by Albert Muriuki January 13, 2010

Jan 13, 2010 (Business Daily/All Africa Global Media) -- Just what would happen if Kenya was to discover large quantities of a rare and precious natural resource that the developing world critically needs?

What would happen if the West decided to attack Kenya, take over the exploitation of the natural resource and try and make our cacophonous political scene more "democratic, free market based and transparent."

What recourse would Kenyans have if a superior more developed country, say the United States, decided that the leadership was too unstable and a danger to the stability of the region and was a hot bed for al- Qaeda, and therefore decided to occupy Kenya, exploit the rare and valuable natural resource and ensure we held periodic elections every five years?

More realistically, what would happen if a private military company, such as Xe Services LLC, formerly known as Blackwater, killed and tortured hundreds of Kenyans while working for its client, the US government, in the war against terror and bombed whole villages in pursuing al-Qaeda; would Kenyan civilians be able to hold the US accountable for a private companies infractions, or would they be left high and dry with no recourse?

This is not farfetched, while operating as Blackwater, Xe Services did launch attacks on behalf of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) into Somalia and Yemen from Kenya while pursuing al-Qaeda operatives. In Sierra Leone, the now defunct South African private military company, Executive Outcomes, received mineral concessions for bringing the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebellion to an end and restoring the Sierra Leonean government. An act that the Sierra Leonean Truth Commission called "the mortgaging of the nations assets," the question is, can the government of Sierra Leone be held responsible for any crimes committed by its employee, Executive Outcomes? In a new book, "War, Commerce And International Law" Kenyan legal scholar, Prof James Thuo Gathii, explores these issues and more. From the war on terror and the Iraq occupation, the book traces the origins of two of the great preoccupations of international law; war and commerce.

From the emergence of the United States as weak state to its current status as the sole global super power, Prof Gathii explores wars and conflicts, including those in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in Iraq and the application of international law and how international law carries with it the legacy of imperialism and colonial conquest. An associate dean for Research and Scholarship and a professor of international commercial law at Albany Law School in New York City, Gathii is no stranger to the Kenyan legal scene, he is an advocate of the High Court of Kenya and a visiting professor at University of Nairobi's Law School and a frequent contributor to the Business Daily.

According to Prof Makau Mutua, the dean at the State University of New York, Buffalo Law School, Gathii's work is not only a pioneering work of African intellectual scholarship at the global stage, it is the only one on the topic he knows of.

At a time when Kenyans are extremely intrigued by the application of international law due to the looming threat of investigations and arrest of suspects of the post-election violence last year by the International Criminal Court (ICC), and having been attacked twice by al-Qaeda, Gathii's book shows how international law is manipulated by powerful countries to make war and confiscate or destroy the property of their enemies, whereas weak nations try to use international law to protect themselves against plunder, pillage, and confiscation of their property by powerful States. At a time of great geopolitical tensions over dwindling resources, Gathii explores the relationship between commerce and war and how they depend and complement each other. We see how the US has evolved from a strong supporter of international law when it was a weak state, to its disregard in recent times.

Gathii argues that one of the reasons the US took a large role in Iraq is because it made its own national security interests the primary aim. As such, if its role meant having no regard for international law, the US was least bothered. It is in examining amorphous wars like the war on terrorism that Gathii explores how weak States like Kenya can safeguard their interests from private contractors hired by more powerful States. Gathii seeks to establish the laws that regulate such private armies and whether these laws are adequate or not.

For Kenyan lawyers, the proliferation of acts of piracy and armed robbery at sea against vessels off the coast of Somalia which has now prompted the international community to intervene and to carry out law enforcement measures in the Horn of Africa region, beckons new opportunities and areas of practice and War Commerce and International Law gives a good grounding of how to utilise domestic and international laws while fighting non State combatants like the pirates.

The book also illustrates the actions that can be used in law to combat private military companies working for State governments.

© 2010 AllAfrica, All Rights Reserved

South African dogs of war in Congo August 27, 1998

Johannesburg (Mail and Guardian, August 28, 1998) - South Africans are embroiled in both sides of the war in Congo. Khareen Pech, William Boot and Ann Eveleth report

South African mercenaries and private military companies swooped into strife-torn Central Africa this week to clinch deals and sharpen the Angolan-led military front in support of the embattled Congolese leader, Laurent Kabila.

A Mail & Guardian investigation has revealed that, contrary to government statements last week denying the involvement of South Africans in the Democratic Republic of Congo's troubles, a wide array of South African-based, military-related companies are playing a strategic role on both sides in the unfolding crisis that could plunge Africa into intra-continental warfare.

Rico Visser, intelligence officer for the Pretoria-based military firm Executive Outcomes (EO), told a small group of journalists last weekend that EO is involved in an operation to restore electricity to Kinshasa, which is powered from the Inga Dam, south-west of the capital. After the port of Matadi on the Congo river, Inga Dam is one of the most strategic points on the western front of the month-old war in the Congo. It is held by Rwandan-backed rebel forces who seized it two weeks ago and is central to their strategy to reclaim Kinshasa and topple Kabila. Operations launched by an EO-led military force are likely to oust the rebels from Inga Dam, and significantly reduce their military chances of winning the war.

Visser has subsequently refuted EO's involvement in the region. Yet last Saturday Visser had placed reporters on standby for a free trip from Lanseria airport to Kinshasa in order to promote EO's role in restoring power to Kinshasa and also to facilitate positive press coverage for Kabila. They claimed to have secured a contract with Kabila and promised to fly the reporters back since EO has regular flights between Johannesburg and Kinshasa.

An SABC crew waited at Lanseria airport for several hours before the flight was rescheduled for Monday or Tuesday. After SABC television news reported the story on Monday, EO angrily called off the free flight, an SABC source said.

Despite Visser's denials, the M&G has learned from reliable sources close to the military group that EO principals have been in contact with Kabila for more than a year and recently negotiated a contract with Kabila's ministers in Kinshasa to supply special VIP protection, sophisticated electronic surveillance services and air combat support.

These same sources say that the planned flight was cancelled after EO failed to receive advance payment from Kinshasa and as a result the contract has not yet been concluded.

EO's involvement with Kabila is closely linked to the recent deployment of Angolan armed forces in the south-west of Congo. According to these and other sources operating in Angola, EO-affiliated commanders have maintained contracts for special support services with the Angolan government. These have included the supply of aircraft as well as fighter jet and helicopter pilots for offensive aerial reconnaissance operations against Unita's embargo-breaking suppliers; offensive intelligence operations and strategic planning. These contracts are run by both London-based principals and Lafras Luitingh, EO's former operations manager, who officially resigned from the group in 1997 but who is still a consultant and de facto operational manager.

A second consortium of affiliated air, cargo, transport and military companies that operates out of smart offices in Rosebank and several premises in Namibia has also secured contracts to supply Kabila's forces with non-lethal support, a senior member of the group said. The consortium has access to strategic airports in the Caprivi strip, northern Mozambique, Zambia, Angola and Malawi. Their operations are focused around lines of support to capital cities and key military bases in the Congo and its neighbouring states.

And this week scores of South Africans arrived with more than 100 white, French-speaking troops in Kabila's home stronghold of Lubumbashi, eyewitnesses said. Their corporate identity is not yet known but they were reportedly hired to defend strategic points outskirting the southern mining capital before an expected rebel attack, security sources say.

Kabila visited South Africa three weeks ago and conducted several military recruitment and fund-raising meetings with clients in Gauteng, according to sources linked to these transport and military companies. He is said to have received about $50-million from a consortium of funders that include South African and Namibian-based businesspeople as well as the Namibian government.

M&G reporters have discovered that the involvement of South Africans in the region is not confined only to Kabila's side. South African-based private military and intelligence companies are also assisting Kabila's challengers - the rival, Tutsi-led power bloc that is chiefly comprised of rebel Congolese as well as Rwandan and Ugandan forces.

A Johannesburg-based corporate intelligence company staffed by former military intelligence officers recently assisted Ugandan defence ministers to procure several South African armoured personnel carriers from local arms manufacturer Reumech.

This transaction was brokered by former South African Defence Force (SADF) officers who have developed links with Kampala in recent months and who are connected to a cast of South African right-wingers.

Key among these is wealthy businessman and farmer Johan Niem"ller, who was recently linked to the South African National Defence Force arms thefts at 44 Parachute Battalion in the Free State. Niem"ller made a fortune through the retail of special-forces fabrics and other equipment to the SADF in the 1980s and at the same time developed close military links with Unita, which he still maintains. Niemoller is also a former member of the Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB) and has been linked to the murder of Anton Lubowski in Windhoek in 1985. Despite being implicated in several sinister plots, Niemoller still runs military supply lines into Africa, security sources said.

Early last year Niemoller began recruiting former SADF soldiers to back Unita forces and troops commanded by former Zairean military leaders who settled in South Africa after fleeing the Congo ahead of Kabila's march into Kinshasa in May 1997. At the time, he consulted a Gauteng-based security expert for strategic advice on ways to plot a sequence of military revolts that would rage through Angola and central Africa. His plan was to "kick the communists out of Africa and put the white man back in power", the security consultant told the M&G.

Recently Niemoller clinched a part of his plan and extended his military influence in the region when he struck a deal with the Mobutuists to establish arms caches in neighbouring territories and received large sums of money from a former Zairean general to recruit hired forces and purchase weapons.

A common factor in many of the military deals shaping the forces in the Central African war is the role of a handful of Mobutu Sese Seko's closest military associates. Former Zairean security police chief General Kpama Baramoto, former special forces commander General Ngbale Nzimbi and former minister of defence Admiral Mudima Mavua topped the list of Kabila's "most-wanted military and civilian suspects" who fled to South Africa as Kinshasa fell last year.

These and other members of Mobutu's inner circle have been plotting to oust Kabila from the Congo since the early days of his own rebellion. Baramoto is one of the richest and most powerful members of this exiled military clique. He led efforts to organise a last-ditch reversal of Kabila's eight-month revolution in January 1997. The plot to retake the former Zaire with the help of 500 heavily armed South African mercenaries involved security firm Stabilco, former EO operative Mauritz le Roux and a handful of former CCB operatives.

The plot fell apart over internal rivalry among the Mobutuists who had failed to clearly negotiate the rescue contract.

But Baramoto did not give up. He revived the plot from the comfort of his luxury homes in Sandton, where he set up house with his five wives and numerous children.

Eyewitnesses to Baramoto's dramatic May 1997 entrance into South Africa say he arrived with suitcases containing more than $100-million and an unknown amount of precious gems. Although the generals pleaded poverty to Minister of Home Affairs Mangosuthu Buthelezi and later to the court, Baramoto's home was subsequently robbed of at least $2-million.

Arrested in December 1997 by South African authorities - on their return from an illicit flight to the Congolese town of Kahemba - Baramoto, Nzimbi and Mavua emerged as the military ringleaders of an international network of Mobutuists bent on regaining power.

The three men admitted in court papers that they had "entered the Congo secretly to attend a meeting to consider whether or not to lend their support to armed resistance to the Kabila regime". They claimed, however, to have decided against joining the rebellion.

But documents confiscated from one of Baramoto's houses suggested otherwise.

According to Buthelezi's affidavit to the court, these included "quotations for arms and ammunition, as well as military personnel ... classified government documents [and] South African identity documents" with the generals' photos issued under bogus names.

Explaining his opposition to the Mobutuist's appeal for political asylum in South Africa, Buthelezi said the generals were "involved in activities which sought to destabilise the Congo in particular as well as the Southern African region in general ... had dealings with persons who have been accused of mercenary activities in other countries [including] elements of the old [pre-1994] military intelligence".

Intelligence sources told the M&G at the time that investigations had revealed the generals had travelled out of the country often to, among other places, Unita's Angolan strongholds and Belgium.

Other sources said the destination of the trip that led to their arrest was not Kahemba, but Unita's Andulo base - and that the plotters they met were in fact senior Unita officials.

Baramoto also met Savimbi during his residence in South Africa, and sources say this produced a joint military training venture between Unita, Hutu militias holed up in Unita strongholds, ex-Zairean Armed Forces soldiers and other Zairean troops. This natural alliance between groups disadvantaged by Mobutu's downfall grew to include other recent losers from Congo-Brazzaville.

A surprise development three months ago, however, saw a sudden reshaping of these predictable groupings in favour of a new opportunism, as sections of the Mobutuists began to co-ordinate their rebellion-plotting meetings with a Rwandan-Banyamulenge (Zairean Tutsis) plan to oust Kabila, whom they had swept to power just 12 months earlier.

Baramoto and his clique of Zairean generals have attended security meetings with Rwandan and Ugandan leaders and have been seen in both Kampala and Kigali in recent weeks, eyewitness sources said.

Africa Confidential has reported that both Baramoto and Nzimbi played a crucial role in the Rwandan-backed rebel capture of Kitona military base. The two generals were able to secure majority support for the Tutsi-led rebels from the former Zairean troops garrisoned there, who have remained loyal to their former commanders.

The M&G can also reveal that a consortium of former military enemies tendered jointly three months ago for a related contract. The bidders included a former Umkhonto weSizwe soldier, an ex-SADF general, as well as a National Intelligence Agency operative and several Johannesburg-based businesspeople.

The prospective buyer was a wealthy Congolese import/export broker based at Johannesburg's Carlton Centre, with links to French funders and pro-Tutsi groups.

The plan on offer included the training of specialist troops, the procurement of light weapons and the supply of strategic support services to back a rebellion to be launched from the eastern provinces of Congo with the aim of finally unseating Kabila.

Alliances in Central Africa are now shifting so quickly and unpredictably that the future of the entire region is uncertain. "The situation presents a real challenge for those who want to look for a politically correct side to join in the war. There is none," said Francois Misser, an established writer on the region.

Copyright 1998 Mail and Guardian. Distributed via Africa News Online.

1,000-MAN MILITIA BEING TRAINED IN NORTH SOMALIA KATHARINE HOURELD Pittsburgh Post-Gazette December 02, 2010

NAIROBI, Kenya -- In the northern reaches of Somalia and at the country's presidential palace, a well-equipped military force is being created, funded by a mysterious donor nation that is also paying for the services of a former CIA officer and a senior ex- U.S. diplomat.

The Associated Press has determined through phone and e-mail interviews with three insiders that training for an anti-piracy force of as many as 1,050 men has already begun in Puntland, a semiautonomous region in northern Somalia believed to hold reserves of oil and gas. But key elements remain unknown -- mainly who is providing the millions of dollars in funding, and for what ultimate purpose.

Pierre Prosper, an ambassador-at-large for war-crimes issues under former President George W. Bush, told AP that he is being paid by a Muslim nation he declined to identify to be a legal adviser to the Somali government, focusing on security, transparency and anti- corruption.

Mr. Prosper said the donations from the Muslim nation come from a "zakat fund," referring to charitable donations that Islam calls for its faithful to give each year. The same donor is paying for both training programs.

Somalia hasn't had a fully functioning government since 1991 and is torn between clan warlords, Islamist insurgent factions, an 8,000- strong African Union peacekeeping force, government forces and allied groups.

Given that mix, the appearance of an unknown donor with deep pockets is troubling, said E.J. Hogendoorn, a Nairobi-based analyst with the International Crisis Group. "We don't know if this unknown entity is operating in the interests of Somalis or their own self- interest," he said in an interview. "If it's a company, there has to be a quid pro quo in terms of [oil and gas] concessions. If it's a government, they are interested in changing the balance of power."

The new force's first class of 150 Somali recruits from Puntland graduated Monday from a 13-week training course, said Mohamed Farole, son of Puntland President Abdirahman Mohamed Farole. The son, who is a liaison between the government and journalists and diplomats, told AP that the new force will hunt down pirates on land in the Galgala mountains.

The range lies 125 miles north of the nearest main pirate anchorage but is home to an Islamist-linked militia which complains that it has been cut out of energy exploration deals.

The Islamist militants, led by Mohamed Said Atom, have clashed with government forces several times this year. A March report by the U.N. accuses Mr. Atom of importing arms from Yemen and receiving consignments from Eritrea, including mortars, for delivery to al- Shabab forces in southern Somalia. Al-Shabab is Somalia's biggest insurgent group and has ties with al-Qaida.

The president's son emphasized that the force was dedicated to anti-piracy, but said he hoped that greater security in the region would bring more investors into "public-private partnerships" with the government. "You cannot have oil exploration if you have insecurity," Mohamed Farole said. "You have to eliminate the pirates and al-Shabab."

Michael Shanklin, who was the CIA's deputy chief of station in Mogadishu 20 years ago, told AP that he is employed by the unidentified donor country as a security adviser and liaison to the Somali government. Mr. Prosper said he is encouraging the Muslim donor nation, which insists on keeping its identity secret, to become more transparent.

The new force will be equipped with 120 new pickup trucks -- which have already arrived -- and six small aircraft for patrolling the coast, Mr. Farole said. No other force in Somalia, including the Mogadishu-based central government or African Union peacekeepers, has air assets.

Mr. Prosper said the Muslim nation is also donating four armored vehicles. A photo provided by diplomats and taken at Mogadishu's airport show two armored trucks made by Ford with gunner's turrets.

In recent weeks, Mr. Shanklin and Mr. Prosper met several Nairobi- based diplomats to discuss the contract between the Puntland and Mogadishu governments and a private security company called Saracen International, Mr. Prosper said in written replies to questions from AP. Mr. Prosper said Saracen is doing the military training and is being paid by the unnamed Muslim nation. Saracen is not providing the militia with any weapons, he said.

Uganda-based Saracen International was named in a March letter written by the Somali president's former chief of staff, Abdulkareem Jama, and obtained by AP that described training for the presidential guard. And it was named in a Nov. 18 statement from Puntland's government announcing the anti-piracy training. Saracen International Chief Executive Bill Pelser said it is "definitely a mistake or a misrepresentation."

Mr. Pelser denied being involved in the training program in Puntland or the one for the presidential guard in Mogadishu, saying he merely made introductions for another company called Saracen Lebanon. Lebanese authorities have no record of a company called Saracen. Mr. Pelser did not respond to requests for contact information for Saracen Lebanon.

Mr. Pelser is a former South African special forces soldier. Like many of his staff, he used to work for Executive Outcomes, a South African mercenary outfit credited with helping defeat rebel forces in Sierra Leone in return for mineral concessions.

© 2010 Post Gazette Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Compiled by: Roobdoon Forum Toronto, Canada

|