| Ramadan Chronicles |

|

Ramadan Chronicles

OCTOBER 2006

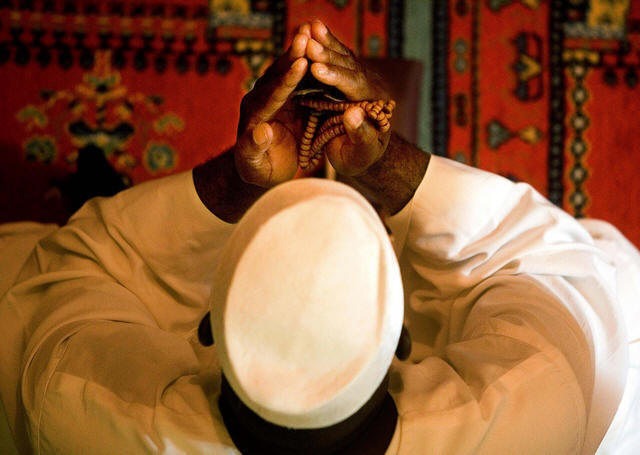

A Muslim prays during the holy month of Ramadan inside a mosque in Lisbon October 6, 2006.

A Kenyan Muslim man pray inside Nairobi's Jamia mosque November 11, 2004 during the holy month of Ramadan.

Kenyan Muslims men read the Koran inside Nairobi's Jamia mosque in this picture taken on November 5, 2004 during the holy month of Ramadan.

Kenyan Muslims pray outside Jamia Mosque on the second Friday of the holy month of Ramadan in the capital Nairobi October 6, 2006.

Elderly Kenyan Muslim men pray at the Jamia Mosque during the first Friday of the holy month of Ramadan in the capital Nairobi, September 29, 2006.

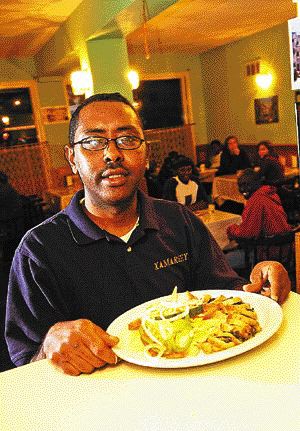

Dining Out Ramadan extras sweeten meal at Xamareey: Moist goat dish entree just the beginning of feast

Liane Faulder The Edmonton Journal 11 October 2006 The Edmonton journal

Abdulkadir Maie of Xamareey with Chi Polo Alla Farmaggio, a Somali spinach-stuffed chicken dish

The shadows were lengthening as we headed for the restaurant, the wistful blue sky of fall a backdrop for the city's bright golden elms, illuminated by a setting sun as if lit for a movie set.

We had a couple of errands to do first, and by the time we arrived at Xamareey, a new Somalian restaurant in the Norwood area, it was 7:30 and nearly dark. The restaurant was almost empty (sometimes a bad sign) and we felt the urge to bolt and go somewhere more familiar, like Tony's New York Pizza, located directly across the way on 111th Avenue.

But the waiter had already caught our eye, and so we sat ourselves at one of the restaurant's handful of tables, each identically adorned with clear plastic tablecloths. Styrofoam cups were at each plate setting, the menu was under the plastic. By now, you will not be surprised to learn the walls are the same colour as pistachio ice cream and department-store lace cafe curtains are on the windows.

Our waiter brings us two big, plastic jugs with brightly coloured lids, full of cold juice, pineapple and mango. As we wait, other patrons wander in, men wearing dark dress pants and pullover sweaters. They speak to each other and the waiter in Somali, sipping juice and laughing.

Our meal arrives quickly. First, the waiter plunks down two gigantic dinner plates full of brown and saffron-coloured rice, fragrant with cumin. Plates of goat and chicken arrive next and it is clear in an instant that the goat was the better choice. It has been boiled, then roasted with a variety of spices. It is so tender and moist it falls off the bone. The chicken, however, is ordinary, flattened with a mallet and brushed with something suspiciously like barbecue sauce.

While we are thrilled with extra food, we explain that we hadn't ordered anything else, in case we were inadvertently getting someone else's food. Then the mystery becomes clear. Our waiter explains we have stumbled into his restaurant after sunset on the first night of the Muslim celebration of Ramadan. Everyone in the restaurant gets more food than usual, because they have been fasting since sun-up and are ravenous. The evening meal, known as iftar, breaks the fast.

We feel somewhat guilty, because we are not Muslim and haven't been fasting. But we are nonetheless pleased to be included in the restaurant's generosity. As if the fruit and samosa stack wasn't enough, our waiter also brings two small, delicious buns, fresh from the oven and stuffed with a creamy cheese.

We can eat no more, but spend a bit more time in the restaurant, watching the other patrons as they thankfully end their day's deprivation. One metal platter after another arrives from the kitchen, often accompanied by a banana, which diners cut into pieces and mix with their rice. Some of the men eat alone and, when they are through, sit themselves at the Internet terminal in the corner, clearly there for communal use. Others meet friends, or come in to purchase take-out.

Xamareey usually serves lunch. But during Ramadan, which ends Oct. 24, doors are closed daily until 7:30 p.m., when the restaurant opens its generous heart to serve a selection of satisfying meals to all comers.

XAMAREEY Address: 9570 111th Ave. Edomton, Canada Phone: 780- 474-7222 Cost: Dinner for two with tax and tip, no liquor: $25

© Copyright © 2006 Edmonton Journal

GOT GOAT? A SOMALI STAPLE OFFERS A MAINE OPPORTUNITY Immigration brings new tastes and traditions, such as goat meat, that can also become a source of new business

TESS NACELEWICZ Staff Writer November 09, 2002

On Friday, the rich smell of roasting goat wafted from the lunch counter at Amei Halaal Meat, a Somali grocery store/restaurant in Portland.

As the meat, rubbed with spices and nestled on a bed of vegetables, cooked in the oven, Mohamed Issak explained how important goat is in the Somali diet.

"We are goat eaters," said Issak, an elder in Portland's Somali immigrant community. "Every Somali family eats goat meat every day."

With a growing number of Somali families in Maine, the demand for goat meat in the state is increasing - and potentially creating a market for a new business opportunity: raising goats for meat. It's an example of the ripple effect that newcomers have on the state.

The University of Maine Cooperative Extension - which provides educational information to the state's farmers - became aware in the past year of the demand by Somalis for goat. The extension currently is conducting a "goat survey" to see if it would be economically viable for Maine farmers to start producing more goats for meat - instead of raising them for dairy products, fiber or breeding stock.

Right now, most of the goat meat that Somali families consume comes from out of state.

"If this is a true market and if they're willing to pay a market price for the animals, this could be a good enterprise," said Richard Brzozowski, an educator with the cooperative extension.

However, most Somalis are Muslim, and Brzozowski said that Maine also likely would need several slaughterhouses where the goats could be killed in the ritual "Halaal" way that Muslims require.

Most Americans turn up their noses at the thought of eating goat, but they belong to one of the few cultures with that attitude. In some countries, goat meat is preferred over beef.

In the United States, ethnic groups that enjoy goat meat include Greeks - who eat baby goat, or kid, on Easter - Hispanics, and people from Caribbean countries.

Maine's Somali immigrants say they like to eat goat because it tastes good. Abdimajid Sharis compared his people's enjoyment of goat to Americans' enjoyment of turkey - a familiar food "that they know how to cook in a good tasty way." When he first came to Maine seven years ago, he would drive to Boston once a month to buy a goat, but now can purchase goat meat at the two Halaal markets in Portland.

According to Issak, there is a strong demand for goat meat in Maine. He estimates there may be as many as 3,000 Somali families in the state, with each family capable of consuming one to two goats a month. At times like the holy month of Ramadan, which began this week, friends and families share meals together after fasting all day, and his family can use 10 to 20 goats, Issak said.

Mumin Abarone, one of the owners of Amei Halaal Meat on St. John Street, which opened just two weeks ago, estimates that store will sell 400-500 pounds of goat meat each month. It gets its supply from New Jersey.

Issak said, "If goat is available in the state of Maine, it will be very helpful for our society."

He hopes that local production would bring down prices, which now are about $4 a pound - too expensive for many immigrant families.

Brzozowski, of the cooperative extension, does not know for certain how many Maine farmers raise goats - that's what the survey asks. But he said goats don't account for a large part of agribusiness in Maine, and the animals typically have been dairy goats raised to produce milk and cheese or as breeding stock.

But about 10 years ago, boer goats - a type of goat bred for meat - were introduced into the United States. Right now Texas is the boer goat capital of the nation, Brzozowski said, even though most of the market for goat meat is in big cities in the Northeast.

However, boer goat production is growing in New England, according to Chris Glynos, owner of the Bethlehem Boer Goat Ranch in Bethlehem, Conn. He's one of the founding members of the New England Boer Goat Association, which formed about a year ago.

"Should farmers in Maine switch over or be interested in raising that type of animal?" Glynos said. "The answer is yes."

Glynos, whose ranch has about 70 goats and who hopes to grow his herd to 300 by next year, called raising goats for meat "the agricultural business of the 21st century" because the demand is so much greater than the supply.

He said Maine already has several boer goat farms. One is BB's Boer Goat Farm in Stetson.

Owner Barbara Bemis said the farm has been in business for three years and is covering most expenses, but has yet to make a profit. Still, she believes the market is improving. The farm's herd of 50 is down to 10 after many of the kids were sold at auction in Massachusetts, but Bemis said a herd grows quickly because the goats often have triplets.

Bemis serves goat - which she described as tasting like mild- flavored beef, but which some people liken to venison - to her family, and believes more people might try it if weren't so expensive.

However, Robert Cassette, who raises dairy goats for breeding and show at Chateau Briant Farm in Saco and sells some extra young goats for meat, said price breaks can't come at the farm level because farmers are just breaking even when they sell their goats.

"I would question that much real money could be made at it," Cassette said. He believes the market is in goat cheese and soap made from goat's milk.

In the meantime, the Amei Halaal Market continues to sell goat to customers, who Abarone said include not only Somalis and immigrants from Sudan but non-immigrant Americans. When they try it, he said, "they like goat."

© Copyright 2002 Blethen Maine Newspapers Inc.

As Ramadan begins, this store bustles

Nolan Zavoral Staff Writer 27 October 2003

Shoppers flocked to a Minneapolis market catering to Muslims to buy the traditional foods served during Ramadan - Islam's holiest month, devoted to personal purification, prayer and charitable acts - which started Sunday.

A deep, lilting, recorded voice recited prayers from the Qur'an over the intercom. In back of the Halal Market, near the intersection of Chicago and Franklin Avs. in south Minneapolis, the meat saw whined, cutting through the rib cage of a skinned goat.

And in a narrow aisle, a cell phone twittered: a wife calling her husband with a reminder.

"She wanted me to be sure and pick up the meat and bring it right home," said Ahmed Moalim, 21, a Somali Muslim who now lives in Minneapolis.

The fasting month of Ramadan already had begun Sunday. Moalim and about 1.5 billion Muslims worldwide - who believe in Allah and his Prophet Mohammed - will signify their commitment to Islam by not eating or drinking, and abstaining from sex and smoking, between sunrise and sunset. Ramadan, Islam's holiest month, is built upon personal purification and also is marked by charitable acts and prayer. The observance falls during the ninth lunar month, when the first revelation of the Qur'an, Islam's holy book, was grasped by the Prophet Mohammed.

During Ramadan, Muslims gather in mosques to pray, in homes to break the fast daily, and in places like the Halal Market to buy what their palates desire and their religion demands.

Fathima Geele, a 32-year-old Somali, drove in from Roseville to buy fresh ground beef and dough: the makings of a meat turnover called "sambusa" or "sanbusa," mentioned by several shoppers as a favorite.

"I did most of my shopping before Sunday, because I knew Ramadan would be Sunday, but then I forgot the ground beef," she said.

Geele spoke and shopped hurriedly, because two of her three children were waiting in the car. Muslim children are not required to fast over day-long stretches until they reach puberty, but Geele said she was already getting her 7-year-old, Isahak, used to the idea.

"He will fast for one or two hours," she said.

And then?

Geele smiled.

"He will say, 'Oh, mom, isn't two hours up yet?' "

Gelle and many other Muslim women wore their traditional long, flowing robes, or "burkas," to the Halal Market, stocking up for the night's breaking of the fast.

Abdinasir Mohamed, a Somali owner of the store, said that the business grossed about $1.6 million a year, and that the first day of Ramadan always produces the most sales. Begun in 1997, Halal - the name refers to the prescribed ways meat is butchered - draws largely from the Somalian neighborhood, Mohamed said, but Muslims also drove in from St. Cloud and beyond.

"They [the Somalis] are refugees, but they are proud refugees," said Xerxes Sarfaraz, a Persian who described himself as a "business consultant" to the market.

"They never expected to live their lives this way. But me, I desire to swim in the mainstream."

Halal Market is among the oldest and largest groceries in the Twin Cities catering to a Muslim clientele. It has five full-time employees and, during Ramadan, four volunteers who stock shelves and run the cash register.

"We [Muslims] all help each other during Ramadan," Mohamed said, explaining the volunteers. "We each have to help the poor. I'm not poor, but they still come to help."

In a corner of the grocery, folded atop boxes, was a red prayer rug that employees use during breaks to pray in a back room; faithful Muslims pray five times daily. Ramadan specials were flagged, everything from corn oil to sugar, and the dates went quickly.

"You must always break the fast with dates, according to [the Prophet] Mohammed," said store supervisor Bile Soldat.

Ahmed Mohamed, 23, a Somali, from Minneapolis, went shopping with his mother, Lul Shide. Mohamed said he woke up Sunday morning, elated that Ramadan had started.

"It's the best day of my life," he said. "It's like celebrating Christmas [for Christians].

"You accept fasting as part of your faith, as commitment to God."

He left to help his mother and then turned and said, "'Soon Wanaagsan. That's 'happy Ramadan,' in Somali. "And may God bless you."

ABOUT RAMADAN

- What: A month-long observance when Muslims seek to be closer to God and to embrace charity and patience.

- When: Began at sunrise, when the new crescent moon was sighted. It takes place in the ninth month of the Muslim lunar calendar.

- How observed: All Muslims who have reached puberty are required to fast each day between sunrise and sunset. They also abstain from smoking and sex during daylight hours.

- Holiest day of the month: It falls on the 27th day, which marks the revelation of the Qur'an, the Muslim holy book, to the Prophet Mohammed in 610 AD.

© Copyright (c) 2003 Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company.

A tired muslim devotee yawns during prayers on the last day of Ramadan in a mosque south of Nairobi January 30.

Kenyan Muslims women read the Koran inside Nairobi's Jamia mosque November 11, 2004 during the holy month of Ramadan.

Kenyan Muslims pray at the Jamia Mosque in Nairobi on the last Friday of the holy month of Ramadan, where Muslims across the world fast from dawn to dusk, November 21, 2003.

The point of a minaret of the old Jamia mosque is seen in Nairobi in this picture taken on November 5, 2004 during the holy month of Ramadan.

|

.jpg)

Xamareey,

the waiter tells us, is what the Somalian capital of Mogadishu used

to be called. The restaurant's menu is small and somewhat puzzling.

In addition to dishes described as Somalian, there are offerings of

a disparate origin, such as Chicken Picatta and Chicken Teriyaki. At

lunch, you can get an egg sandwich for $3.50. But someone has

recommended this restaurant to us as an authentic African

experience, and so we ask the waiter to suggest something Somalian

he thinks we'd like. Warily, he recommends the home-style baked goat

($9) and the chicken, fast-fried Somali style ($9.95).

Xamareey,

the waiter tells us, is what the Somalian capital of Mogadishu used

to be called. The restaurant's menu is small and somewhat puzzling.

In addition to dishes described as Somalian, there are offerings of

a disparate origin, such as Chicken Picatta and Chicken Teriyaki. At

lunch, you can get an egg sandwich for $3.50. But someone has

recommended this restaurant to us as an authentic African

experience, and so we ask the waiter to suggest something Somalian

he thinks we'd like. Warily, he recommends the home-style baked goat

($9) and the chicken, fast-fried Somali style ($9.95).

We

are just finishing up our piles of rice when more food arrives. Our

waiter brings tasty samosas stuffed with hamburger and onion, as

well as a flat, slightly sweet pastry with the consistency of a

doughnut. Motioning as he speaks, the waiter explains we should

place the samosa on top of the pastry and eat them together. The

sweet and savoury flavours are, indeed, a complement to one another.

Fast on the heels of the pastry and samosa is a bowl of fruit

cocktail.

We

are just finishing up our piles of rice when more food arrives. Our

waiter brings tasty samosas stuffed with hamburger and onion, as

well as a flat, slightly sweet pastry with the consistency of a

doughnut. Motioning as he speaks, the waiter explains we should

place the samosa on top of the pastry and eat them together. The

sweet and savoury flavours are, indeed, a complement to one another.

Fast on the heels of the pastry and samosa is a bowl of fruit

cocktail.